The Septuagint's Missing Hare

What should we make of the Talmud's list of differences?

The legend I discussed last week about the Greek translation of the Bible comes from the Letter of Aristeas, written in the 2nd century BCE. It made its way into rabbinic literature, appearing in various different versions in the Talmud and the Midrash, the vast repositories of Jewish thought of the 2nd to 6th centuries CE.

Most of the rabbinic versions mention the miracle of 72 translators each locked away in a separate cell, unable to communicate with each other, yet producing identical translations of the Hebrew bible. Where they differ from the earliest versions of the legend is that they list several changes made by the translators which subtly altered the meaning of the original Hebrew text.

Among the changes they made was God’s declaration ‘Let us make man in our image’ in the first chapter of Genesis. The translators changed it to ‘I will make man…’. They similarly changed his statement at the Tower of Babel from ‘Let us go down and mix up their speech’ to ‘I will go down….’ and they altered Jacob’s indictment of two of his sons, from ‘in their anger they slew a man’ to ‘…. they slew an ox’. In some versions of the legend they made ten changes, in others thirteen. The changes end with what seems like a touch of humour: they omitted the hare from the list of forbidden foods, because the name of King Ptolemy’s wife sounded like the Greek word for hare.

When we look through the list of changes it becomes obvious that each one was made to counter a theological objection, presumably one that was current when the changes were made. Having God speak about himself in the singular rather than the plural was a riposte to those who used the original Hebrew text to support their belief in two gods. Jacob’s original criticism of his sons suggests that their slaughter of the inhabitants of Shechem was the result of their anger, which implies that the translators were trying to avoid the charge that they had acted unjustly (which of course they had!).

Elsewhere they clarified passages that might be misinterpreted to suggest that God had not created the sun, moon and stars, or which suggested that Moses had to travel with his wife and children on a donkey because he couldn’t afford a camel or horse. [I have pasted a translation of one of these lists of changes at the end of this article, if you would like to see them all.]

The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Bible that we have today, contains some of the changes mentioned in the Jewish version of the legends, but by no means all. The version of the Septuagint we have today has been edited considerably over the years, so it could be that the missing changes have simply dropped out.

Equally, it may be that the missing changes never were in any of the Greek translations, that the rabbinic versions of the legends serve a different purpose altogether. There are many difficulties with the original Hebrew text of the Torah, a good proportion of rabbinic literature is dedicated to clarifying inconsistencies, explaining difficult meanings or harmonising contradictions. It could be that the changes are the Talmud’s way of compensating for some of the difficulties in the Hebrew Torah, because the text itself cannot be amended. No matter how problematic the original Hebrew text might be, it is sacrosanct. It can be amended in translation, but never in the original.

According to ancient Jewish tradition, the Hebrew text of the Torah is sacrosanct because it is an exact transcription of God’s word to Moses, dictated during the 40 years that the Israelites wandered through the wilderness. On a practical level it is sacrosanct because the Talmud derives many Jewish laws from the Torah text, very often relying on just one letter or the spelling of a particular word to support its ruling. If the text was allowed to be fluid, if different copies of the Torah contained different spellings, Jewish law would lose its authority.

But this too is a problem. How can one ensure that a text which is thousands of years old is exactly the same today as when it was first written? For most of its history, until the introduction of printing, the Bible was copied from one manuscript to another. Even the most assiduous of scribes is liable to make mistakes. Once a mistake is made, the next scribe will not only copy it into the manuscript he is working from, he is likely to add his own errors as well. So how can the integrity of a text, no matter how holy, be preserved over thousands of years?

The answer of course is that it can’t. But that didn’t stop people from going to astonishing lengths to try to make sure that the text of the Torah was immaculate, unchanged from the words which they believed God had dictated to Moses all those thousands of years ago.

The people who laboured at this task between the 6th and 9th centuries lived mainly in Tiberias, on the Sea of Galilee and in Jerusalem. They were called Masoretes, from the Hebrew word meaning tradition. Their techniques for standardising the Hebrew text included counting the occurrence of every word, making marginal notes when spellings differed and devising a complex system of annotations to guide future scribes in their work.

Like many craft workers in the ancient world, the Masoretes passed their skills down through their families, from father to child. The most distinguished family of Masoretes was that of Ben Asher and it was they who were responsible for producing the codex on which all subsequent copies of the Hebrew Bible were based. (A codex is an ancient form of book, in which, like books today, all the sheets are bound together on one edge). This particular codex, written around 930 CE, has a sad history. It was preserved intact for many centuries in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo where it was the pride and joy of the local Jewish community. They called it the Crown of Aleppo. It is more commonly known as the Aleppo Codex.

1n 1947, after the United Nations voted to partition Palestine and grant independence to the State of Israel, riots broke out in Aleppo. The Great Synagogue was attacked and it was believed that the Aleppo Codex had been burned. In fact much of it was secretly rescued and ten years later was smuggled to Jerusalem where it is now in the Israel Museum. Large chunks of the codex had vanished though, mainly from the Torah, the first five books of the bible. There is still fierce controversy over what happened to the missing pages, as Matti Friedman recounts in his masterful and unmissable book, The Aleppo Codex.

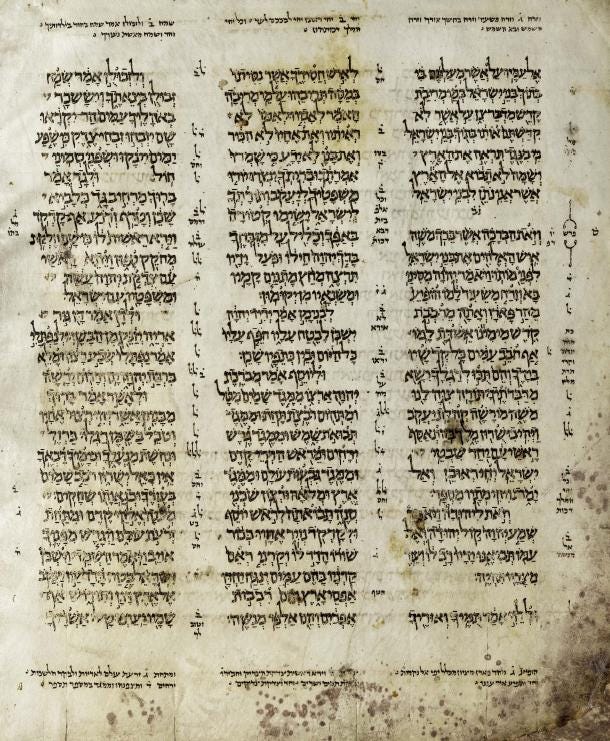

Before it was partially destroyed, the Aleppo Codex was one of only two fully authoritative copies of the Hebrew Bible in the world. The other, which scholars believe was based on the Aleppo Codex and is therefore a little younger, is in the Russian National Library in St Petersburg. It is known as the Leningrad Codex and it is now the oldest, fully intact, Hebrew Bible manuscript in the world. It differs in a few places from the Aleppo Codex but the differences are negligible as far as the meaning of the text is concerned.

Were it not for the existence of the Leningrad Codex the partial destruction of the Crown of Aleppo would have destroyed the Bible’s textual link with the past. Fortunately, by the time the Aleppo Codex was damaged, modern scholarship had developed the tools to attempt a reconstruction. When the scholar Mordechai Breuer published the Crown of Jerusalem bible in 2003, the Aleppo Codex came back to life, now for the first time in print rather than in manuscript.