How to Write Yourself into History

The Letter of Aristeas and the legend of the Septuagint

I wrote last week about the Greek Jews in Alexandria who composed the Sibylline Oracles. Originally a collection of prophecies, myths and apocalypses written from a Jewish perspective, the Oracles were given a Christian flavour by some of the early followers of Jesus.

The Sibylline Oracles are historically interesting but they didn’t have any great impact on either Judaism or Christianity. The Greek Jews in Alexandria had a far more important consequence on the history of religion: they were responsible for proving one of the most fundamental articles of Christian faith, the belief in Mary’s virginity. It was the result of the translation of the Bible into Greek, made in Alexandria around the 3rd or 4th century BCE. It was the first ever translation of the Hebrew bible into any language.

The Greek translation became known as the Septuagint; the word means Seventy. We don’t know the full history behind the translation, who the translators were, or what motivated them to translate the Bible. But there is a fascinating legend which, like all legends, probably contains a degree of truth.

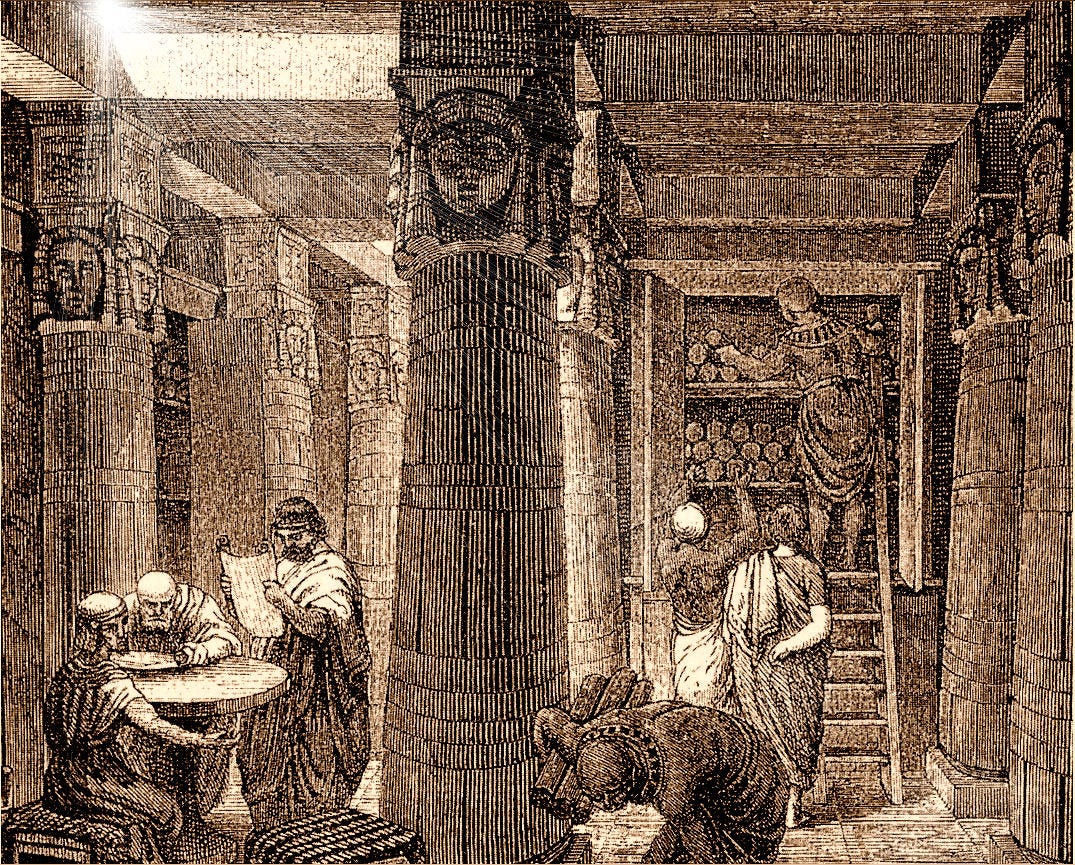

The earliest version of the legend is contained in a document called the Letter of Aristeas, written in the 2nd century BCE. It is based on an event that happened when the Egyptian king, Ptolemy II, commissioned the building of a library in Alexandria. The library was to be the greatest in the world, containing Greek translations of every known book ever written, anywhere.

A team of scholars was hired to translate the pile of foreign books that had been bought, borrowed and pilfered for the library. They breezed their way through complicated works like the two million verses attributed to the Persian philosopher Zoroaster. But they discovered a problem which threatened to undermine the library’s status as the unchallenged repository for the whole of the world’s literature. According to Aristeas’ Letter, they were stumped by one text whose language they could not understand. It was the Hebrew Bible.

This is the first of several assertions in the Letter of Aristeas which make us doubt the author’s credibility. The idea that nobody in Alexandria could understand Hebrew is unrealistic. The city had a large Jewish community, some of whom were bound to understand Hebrew. Also, Egypt and Israel shared a border; traders and merchants went back and forth between the two countries all the time. Yet Aristeas implies that nobody in Alexandria could read Hebrew, that there was not a soul who could decipher the strange characters in which the language was written, nor understand the words the characters formed.

The king wasn’t bothered by the problem. He simply instructed his librarian, Demetrius, to despatch a delegation to the High Priest in Jerusalem, asking him to send a team of Jewish scholars to Alexandria to translate the Bible into Greek. Aristeas’s Letter was written a century or so after the events he is describing, but he has no problem in writing himself into the story and fabricating a conversation between himself and the king. He says that he told the king that there were 100,000 Jewish slaves in Egypt who had been taken captive during a war. Aristeas claims to have suggested that the king should free the slaves and should mention this when writing to the High Priest. It would make the High Priest far more willing to agree to his request. The king duly freed the slaves and asked Aristeas (who had not yet been born) to be part of the delegation to Jerusalem.

Aristeas’s letter is long and convoluted. He spends pages and pages describing the sights the delegation saw on their way to Jerusalem, the splendour of the city itself, its architecture, treasures and its great renown. He writes about the success of his mission, of how the High Priest agreed to send a team of translators to Alexandria.

At this point his account begins to sound even more contrived. He tells us that the High Priest sent 72 translators, six from each of the 12 Israelite tribes. It sounds neat but it was too tidy. The ancient, Israelite tribal system had long since broken down; most people no longer knew which tribe their ancestors had belonged to. Only the priestly tribe had retained its distinctive identity.

Aristeas’s account becomes even more fanciful when he describes a week-long banquet that the Egyptian king allegedly held in the Hebrew translators’ honour. Over the course of the feast Ptolemy posed 72 profound metaphysical and philosophical questions to the 72 translators. Aristeas ponderously records each and every question, along with the translators’ responses. The account of this symposium takes up far more room in Aristeas’s Letter than anything else.

Finally, when all the questions are turgidly disposed of, Aristeas returns to his original theme. He recounts how the translators were conducted to well-appointed quarters on the sea shore of the island of Pharos. They were given all the materials they needed to collaborate on their translation and, exactly seventy two days later, the seventy two men proudly presented Demetrius with a copy of their work. The Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible was complete.

Aristeas’s account is the earliest source to indicate that the Septuagint was written in Alexandria. The scholarly view today is that it was translated from Hebrew by a Greek speaking Egyptian Jew, for members of Alexandria’s large and flourishing Jewish community whose grasp of their ancestral Hebrew tongue was diminishing. One reason for this theory is that the dialect of Greek used in the translation is similar to that found in other Egyptian documents from the same period. The Septuagint even contains a few Egyptian words. This suggests that the translation was made by Greek speaking Egyptians. Not, as Aristeas suggests, by Hebrew speaking foreigners from Jerusalem.

The legend was popular in its day. It crops up a second time in the writings of Philo, a Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria from about 25 BCE to 50 CE. Philo doesn’t agree with every detail of Aristeas’s account. He does agree that the translation was commissioned by Ptolemy II and he relates the arrival of envoys from Jerusalem, the lavish banquet and the symposium instigated by the king. But instead of the 72 translators collaborating to produce the best possible version, Philo’s delegates each worked on their own to produce their own version. And yet miraculously every version they produced was identical, word for word, as if the translators were divinely inspired.

The miracle that Philo hints at became more pronounced as the legend developed over the coming centuries. In later versions, there were 70 translators, not 72, hence the name Septuagint, meaning 70. Astonishingly they didn’t just produce 70 identical Greek versions of the Pentateuch; they did so despite being locked into separate cells, unable to communicate with each other.

Towards the end of the second century CE, the Church Father, Irenaeus of Lyons, wrote that Ptolemy separated the translators so that they couldn’t conspire to falsify the truth in the Scriptures. Irenaeus was not being paranoid. He wants to emphasise the miraculous, ineffable nature of the Septuagint, and to stress that even if the translators had wanted to conceal the truth they were not able to do so. In Irenaeus’s eyes, the miracle stopped the Jewish translators from falsifying the Bible, from eliminating prophesies which he believed foretold the coming of Jesus. Aristeas’s legend was evolving into polemic. And the translation was becoming a battleground.

The battle was over the meaning of the Hebrew word almah in Isaiah 7,14. It means young woman. The verse translates as ‘behold the young woman is pregnant and will give birth to a son.’ The Septuagint however translated almah by the Greek word parthenos, which can mean virgin (though not necessarily). The apostle Matthew took the Septuagint’s translation of almah as parthenos as proof that Isaiah had foreseen that a virgin would give birth.

Of course, the Septuagint, written two or three hundred years before Jesus’s birth was oblivious to the implications of its choice of word. The translators could not have foreseen that their rendering of Isaiah’s prophecy of a young woman giving birth would lead to the doctrine of Mary’s virginity.

We might speculate whether Christian doctrine might have been different if the Septuagint had never been written, if the Greek-speaking Jews in Alexandria hadn’t wanted a bible written in the language they understood. Or if whoever made the translation hadn’t translated almah as parthenos. History is rarely straightforward.

The translation of the Septuagint translation had other consequences too, particularly for the Jews. We will look at those next week.