A Land of Contradictions

Syria’s Unusual Jewish History

Syria, so much in the news at present, has a long and continuous Jewish history, stretching from biblical times until the 20th century. Damascus, mentioned 35 times in the Hebrew Bible was, according to the Book of Kings, once a garrison town for King David’s troops.

The many centuries of Jewish life in Syria were mostly peaceful, though the calm was shattered from time to time. The most notorious incident was when Damascus became the scene of one the 19th century’s worst antisemitic outrages. Sparked by the disappearance of an elderly Italian monk and his servant and fed by an outbreak of rumours that they had been abducted and murdered by Jews, the riots, arrests and deaths that followed made the event one the very few blood libels ever to take place in a Moslem country.

The Damascus Affair, as it became known, hit the newspapers across Europe and America. The press mostly believed the rumours and reported the affair sensationally, showing very little sympathy for the dozen Jews who had been falsely arrested and tortured, four of whom had died. The Jewish communities of England and France were galvanised, sending high powered delegations to Damascus, who unsuccessfully lobbied for the captives to be released. The matter was only resolved when Austria became involved, after they realised that the affair was threatening their economic interests.

Syria’s second city Aleppo, the site of such recent devastation, has a similarly deep Jewish connection. Known in biblical times as Aram Tzovah, and mentioned in the Book of Psalms, Aleppo became central to biblical history in the late 14th century when a manuscript of the Bible, known as the Ben Asher codex, arrived in the city.

For 500 years the Ben Asher codex had been regarded as one of only two fully accurate copies of the Hebrew Bible, in which every letter, vowel and cantillation note was inscribed correctly. The codex (an old type of book) was the work, over several generations, of the Ben Asher family in 11th century Tiberias. They had dedicated their lives to studying biblical manuscripts and sifting evidence from the Talmud and other ancient sources. Their aim was to reconstitute the correct text of the Bible which had been corrupted over time by miscopying and scribal errors. .

When the Crusaders invaded the Land of Israel in 1099, the Ben Asher codex was smuggled out of the country to keep it safe. It was taken to Fustat, the old city of Cairo, in Egypt. Maimonides, the doyen of medieval Jewish scholars, saw it there and testified to its superiority over all other biblical manuscripts he had seen.

For reasons now forgotten, it left Fustat and was taken to Syria around the year 1375 where it was stored in the Great Synagogue in Aleppo. The local community treated it as an object of pride and veneration, bestowing upon it the title Crown of Aleppo and keeping it safe in its vault for nearly 600 years. Then in 1947, when the United Nations voted in favour of the establishment of the State of Israel, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Aleppo. The synagogue was set on fire and the codex nearly destroyed. Much of it was saved from the flames, but a considerable number of pages were missing, some possibly burnt, the majority more likely to have vanished into the hands of unscrupulous collectors and dealers. One of the missing pages contains the commandment Thou Shalt Not Steal. The remainder of the Crown of Aleppo is now in Jerusalem’s Israel Museum, housed in the Shrine of the Book, alongside the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Perhaps the most remarkable memorial to Syria’s long Jewish history however was not discovered until 1932. Archaeological excavations were taking place at the site of a ruined city overlooking the Euphrates river. Known as Europos, it had been founded around 300 BCE by the Syrian-Greek king Seleucus Nikator. The Romans captured it in 165 CE and turned it into a fortress town. They gave it the name Dura, meaning harsh or tough, presumably because of the terrain and its apparent invincibility. The site has been called Dura-Europos ever since.

Nearly 100 years later Rome’s eastern rivals, the Sassanian Empire, besieged Dura-Europos. To defend it, the Roman army constructed earthworks, filling the streets and buildings on the edge of the city with piles of rubble. Archaeologists began excavating the rubble in the 1920s and were still working on the site in 1932.

The leader of the expedition, Clark Hopkins, described what happened when the excavation reached a 40 foot long wall that seemed to conceal something of interest.

The signal was given and the best of our pick-men undercut the blanket of dirt concealing the west wall. Like a blanket or a series of blankets, the dirt fell and revealed pictures, paintings, vivid in colour, startling; so fresh it seemed they might have been painted a month before. There was a mighty series of paintings, the scenes continuing from the north corner along the whole forty feet of wall . . . It was a scene like a dream! In the infinite space of clear blue sky and bare grey desert, there was a miracle taking place, an oasis of painting springing up from the dull earth. The size of the room was dwarfed by the limitless horizons, but no one could deny the extraordinary array of figures, the brilliant scenes, the astounding colours. What did it mean? Who was the tall figure leading a host from the fortress walls of a city, and what meant those splotches of red and yellow above the walls in the high corner of the painting?

As they dug further the nature of the excavation became clear. They had uncovered an ancient place of worship, its walls covered in paintings, the ceiling studded with ornate tiles. That it had been a synagogue was evident, both from the inscriptions among the paintings, written in Aramaic, Persian and Hebrew and from the pictures themselves. They were all scenes from the Hebrew Bible.

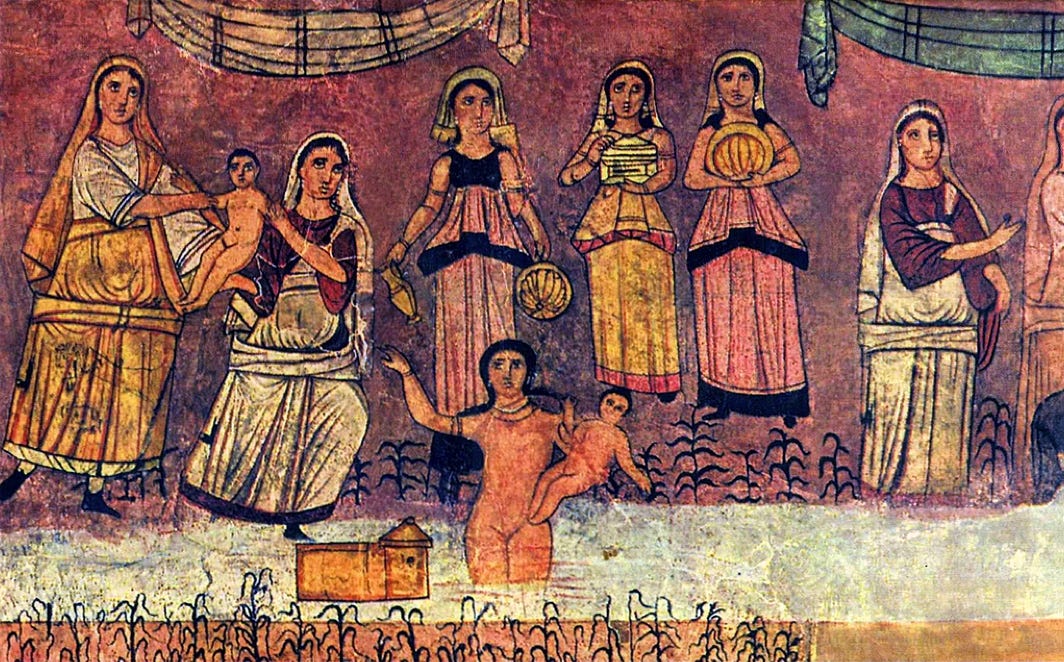

Nobody had ever seen a display of Jewish artwork like it. Indeed, nobody imagined that anything of the sort could possibly exist. After all, the second of the Ten Commandments forbids making ‘an image or likeness of anything in the heavens above or the earth below’. This meant, most people assumed, that Jews were prohibited from making any sort of figurative representation. Yet here was a synagogue, dating from the 3rd century CE, full of pictures of biblical scenes. They included three paintings of Moses, one of him as a baby, being placed in a basket in the river, a huge one of him splitting the Red Sea and another of him causing water to flow from a well, a story recounted in the Book of Numbers. There were pictures on the walls of hordes of Israelites crossing the desert, of Samuel anointing David, of Queen Esther, Ahasuerus and Haman and many others. This was not an old synagogue with a few paintings in it; it was a gallery filled from floor to ceiling with artwork, not an inch was unpainted. Preserved in a dry climate in a space filled with earth so that no air could get to it, the quality of the representations was astounding.

The Dura Europos pictures are now well known. The original walls were cut out and are stored in a museum in Damascus, though access to them has long been prohibited and there is no way of knowing if they are still intact. There are however good reproductions of the synagogue walls in the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv and available online. And since 1932 other illustrated ancient synagogues have been discovered in the region, though none are as elaborate as Dura-Europos.

Unsurprisingly, many scholars have researched and written about Dura Europos. Dozens of theories have been put forward in explanation of the images. One, for example, argues that the depiction of the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, who are carrying shields and seem to be marching in formation, suggests that the builders of the synagogue may have been soldiers in the Roman army, quartered in Dura-Europus[1]. Another points out that a section of one wall, containing pictures of children at various stages of their lives, was designed for the children of worshippers attending the synagogue.[2] A third argues that the entire cycle of paintings is a ‘visual midrash’, a graphic tale based on biblical narratives and legends in circulation at the time the synagogue was built.[3] One of the earliest studies of the paintings saw in them the influence of Greek and Persian legends.[4] There are many other, similar theories.

As to the question of how a synagogue can contain artwork, there is in fact no formal prohibition against it. The commandment against making images is discussed at length in the Talmud, which clearly understands it to be merely a prohibition against making idols for worship. In any event, the builders of the Dura-Europos synagogue knew nothing of the Talmud; they lived before it was compiled. When the Romans piled their earthworks on top of the synagogue, Jewish law was still in an early phase of evolution. The Mishnah, the code of law on which the Talmud is based, had only recently been formulated, it was still circulating orally and there is no way of knowing whether the Dura-Europos Jews, living in what seems to have been an outpost, knew anything about it.

The artwork in Dura-Europos was outstanding, but that is not the only significance of the site. Dura-Europos is one of the earliest surviving examples of ancient Jewish architecture, just one of many instances of the variety of Jewish life that Syria played host to, over several thousand years.

[1] https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5703/shofar.30.3.1

[2] https://www.thetorah.com/article/retelling-the-story-of-moses-at-dura-europos-synagogue

[3] https://rsc.byu.edu/scriptures-modern-world/dura-synagogue-visual-midrash

[4] https://www.jstor.org/stable/27924866.