The Jewish populations of Europe reacted excitedly to Napoleon’s rampage across the continent. They knew that France had abolished all anti-Jewish legislation, and that Napoleon was committed to civic equality in all the territories that he conquered. After centuries of persecution, Europe’s Jews dared to hope that emancipation was on its way.

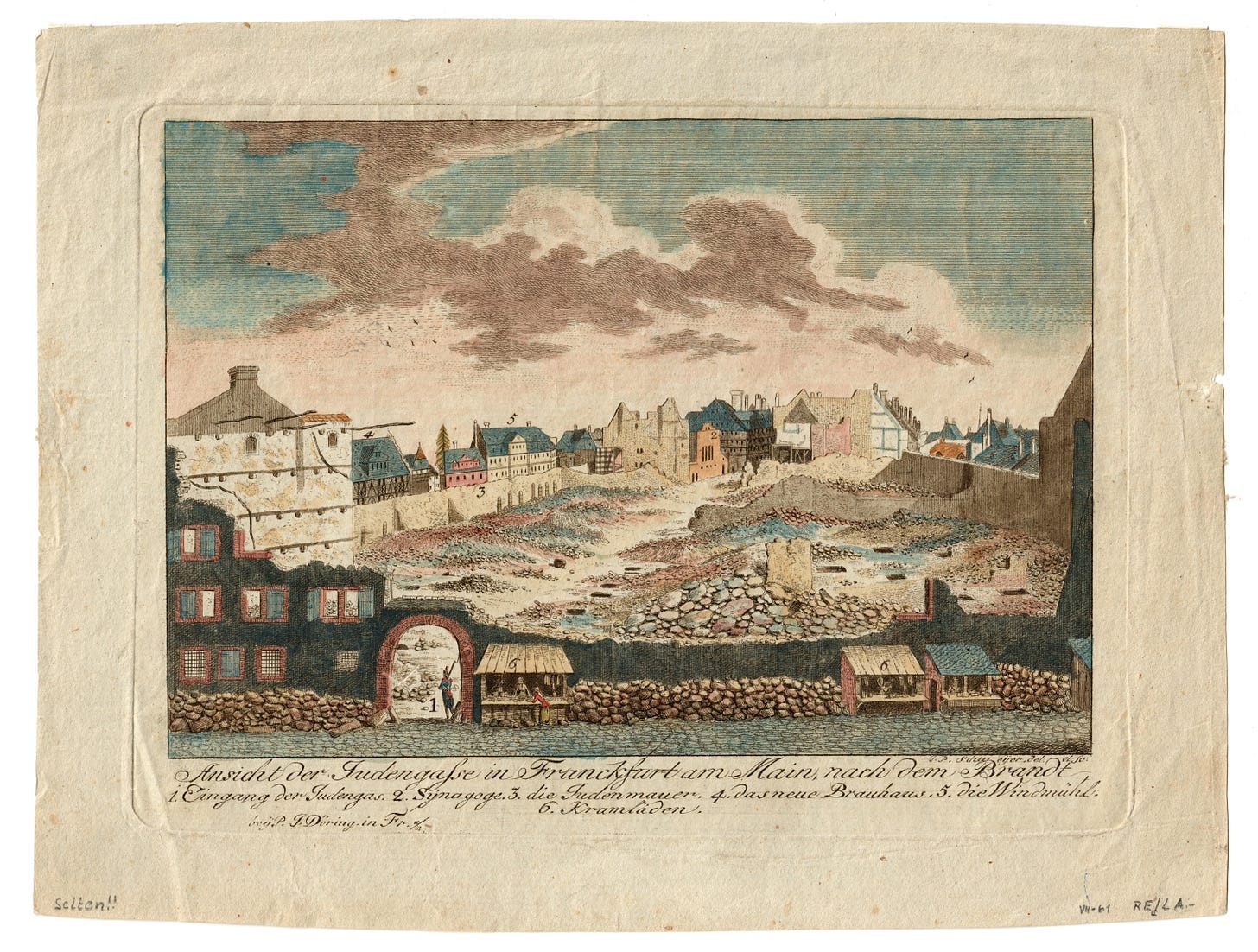

Expectations ran particularly high in Frankfurt. Of all Europe’s cities, Frankfurt was where Jews found life especially hard. Conditions in the Judengasse, the ghetto where they were forced to live, were even worse than in most places: the small, overcrowded, medieval buildings were crumbling around them, there was no sanitation, disease and poverty were rife. Unlike in many cities, Jews were locked in to the ghetto every night, and during the day too over the Easter holiday. They were only ever allowed to enter the main city for commercial purposes, never for leisure or entertainment.

If they did come into the city they could only walk in pairs, no more than two abreast. They were forbidden from entering an inn or a public square, they couldn’t go anywhere near the cathedral and, if they needed to enter the Town Hall, they had to go in through a back door. No wonder they prayed that Napoleon would conquer the city and emancipate them.

They thought their prayers were answered when Napoleon’s forces laid siege to Frankfurt. Fearing that if the city fell, the mob would turn against them, the Jews fled from the ghetto, taking their belongings with them and seeking shelter across the river. As they fled, a burst of cannon fire from Napoleon’s artillery went astray, missing its target and landing instead in the Judengasse. The empty ghetto went up in flames and the Jews found themselves homeless. The Senate had no alternative than to allow them into the city, to live alongside the Christian population. For the Jews, things seemed to be on the up.

For Meyer Amschel Rothschild, one of the residents of the ghetto, things had improved some years earlier. He had been born in 1744, into a lower middle class family, neither wealthy nor poor. His father, who had died when Meyer Amschel was 12, had been a small time pawnbroker and silk merchant. Like all children in the ghetto, Meyer Amschel received a traditional Jewish education. As soon as he was old enough, he worked in the family business, running errands or helping out with simple tasks. His big break came in his early teens when, through family connections, he was offered an apprenticeship in Hanover, in Wolf Oppenheim’s banking house. The Oppenheims were a prominent Jewish family who served as court factors across Germany and Austria, providing finance and resources for local rulers. The firm had been founded by Wolf Oppenheim’s grandfather Samuel Oppenheimer, who provided finance to the Austrian emperor Leopold I, equipping his armies during his 1673-9 war with France.

From a young age, Meyer Amschel had been fascinated by coins. Working at the Oppenheim bank brought him into contact with many different types of coin, both collectors’ items and currency from across Europe. By the age of 18 he was becoming an expert in numismatics. When a wealthy collector in Hanover commissioned him to acquire coins on his behalf, Meyer Amschel branched out into a new career. He returned to Frankfurt and began dealing in coins.

In June 1765, Meyer Amschel met Crown-Prince Wilhelm at a fair in Frankfurt. The Crown-Prince had already heard of Meyer Amschel; he was a friend of the man who had first commissioned him to obtain coins for him and, as a coin collector himself he was keen to meet the young dealer. The two men, who were of similar age, struck up a business relationship, such that by 1769 Rothschild felt comfortable writing to him, gushingly, stating: “I now stand ready to exert all my energies and my entire fortune to serve Your Lofty Princely Serenity whenever in future it shall please you to command me. A special and powerful incentive to this end would be given me if Your Lofty Princely Serenity deigned to grace me with an appointment as Court-Factor.”

The Crown-Prince agreed to Rothschild’s request and at the young age of 25 he began his career as court-factor. It was an honorary appointment that came with no special privileges; Meyer Amschel still lived under the same restriction as all other Jews, still obliged to live in the ghetto. But the appointment gave him status and was undoubtedly good for business. He printed catalogues, bound in gold-embossed leather, of the coins he had on offer. He signed his catalogues with the words “Mayer Amschel Rothschild, The Lofty Prince of Hesse-Hanau’s Court-Factor, resident at Frankfurt-am-Mayn” and sent them to distinguished customers, including the King of Bavaria, the Duke of Weimar and his friend the Crown-Prince.

Rothchild’s business went from strength to strength. He began to branch out. On one occasion, the Crown-Prince asked him to cash some English bills of exchange he had received from George III; payment for providing him with soldiers to fight in the American civil war. It was Rothschild’s first banking transaction; he soon followed it with deals with other German princes and rulers.

By the time Napoleon laid siege to Frankfurt, Meyer Amschel was a wealthy man, married to Gittel Schnapper, parents of five sons and five daughters. He was powerful and influential and it is just as well he was, because Napoleon failed to live up to his promise of civil equality. It fell to Meyer Amschel to work to try to raise the fortunes of Frankfurt’s Jews.

Civil equality had failed to materialise, largely because Grand Duke Dalberg, the man who Napoleon had appointed as the local sovereign, wanted to levy an exorbitant fee on the city’s Jews in return for their freedom. Jews were still banned from the city’s main squares, inns and coffee houses, they still had to pay a special Jewish tax and, in addition, they were now told they had to leave the homes they had rented in the Christian quarter after the fire in the Judengasse, and return to the newly rebuilt ghetto. The Jews had not paid the fee that Dalberg demanded, and he refused to emancipate them.

However, Grand Duke Dalberg always needed money. He had been refused credit by the Christian bankers, had borrowed instead from Rothschild. Rothschild was courteous and generous to the Duke, an attitude that paid dividends when the two men entered into negotiations.

They eventually agreed that Frankfurt’s Jews would be granted full equality in return for the payment of 440,000 guilders; Rothschild offered to pay one quarter himself and the community agreed to raise the rest between them. Rothschild proudly wrote to his sons telling them that they were now citizens. A local Jewish magazine wrote: “Great is the joy of the Jews over the improvement of their unsatisfactory situation and [it is] easy to explain. Already many are registering to join the new National Guard. All are filled with ardent desire to prove their availability to the State.” Centuries of prejudice and discrimination were forgiven, just like that.

Mayer Amschel Rothschild was one of several Jewish court agents who became fabulously wealthy during the18th and 19th centuries. But most of their stories have been forgotten. One reason that the Rothschild name and dynasty has survived can be traced back to the decision he made, to send each of his five sons to a different European financial capital. By the early 19th century there were Rothschild banks in London, Paris, Naples, Vienna and Frankfurt. Meyer Amschel realised the importance of building a pan-European presence for his business, long before anybody else. It was the most important strategic decision he made.

There is a second reason for the Rothschilds’ success too. It has to do with the power of public image and spin. After his patron, the Crown Prince, fell out with Napoleon, the Emperor told his soldiers to seize all his wealth. He was stripped of much of his fortune but managed to save quite a lot. Rothschild helped him to save it. Between them they smuggled consignments of gold, art, jewellery and other treasures to trusted associates in England, beyond Napoleon’s reach. Rothschild took four crates himself and hid them in the cellar under his house in the ghetto.

Just four crates, out of a total of maybe 200. But that is not how the story was reported. After Napoleon’s defeat his sons manufactured the legend that the Crown Prince had entrusted all his money to their father. They commissioned two paintings, one showing the Crown Prince giving Rothschild all his treasures, the other showing him returning them. In a speech in London, his son Nathan declared: “The prince gave my father all his money; there was no time to be lost; he sent it to me. I had 600,000 pounds arrive unexpectedly by the post; and I put it to such good use that the prince made me a present of all his wine and his linen.”

It wasn’t true but the story served its purpose. If a Crown Prince can trust the Rothschilds with all his money, then so too could anybody else. There is nothing more important, when building a banking empire, than trust. And Meyer Amschel Rothschild, and his sons, knew how to show people they could be trusted.