The first Jews to set foot on the American continent arrived in 1492 with Christopher Columbus. They were all conversos, born into Jewish families that had been converted to Christianity in Spain and Portugal. Among them were Columbus’s bursar, Alfonso de Calle, the surgeon Rodrigo Sanchez and the multilingual Luis de Torres, taken on as a potential translator. Some people even maintain that Columbus himself was Jewish.

The early converso settlers took little interest in their ancestry. It wasn’t until the Dutch arrived on the continent, 140 years later, that the first Jewish community was established and the first synagogue built.

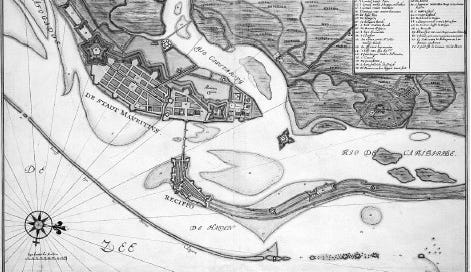

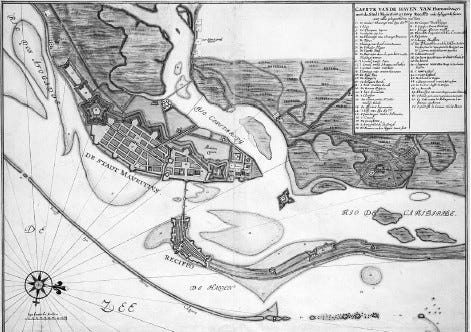

The Dutch arrived in 1630, landing in the port of Recife and seizing a large area of northern Brazil. The Netherlands, a Protestant nation free from the threat of Inquisition and with a declared policy of religious toleration, had become a haven for converso refugees fleeing Spain and Portugal, in order to return to Judaism.

The government of the Netherlands appointed the Dutch West India Company to lead the invasion of Northern Brazil. They aimed to colonise the territory and seize the massive Brazilian sugar industry from the Portuguese. Before sailing, the Dutch West India Company declared that the lands they were hoping to conquer would adopt the same policy of religious toleration as the Netherlands itself. For the Dutch Jews, and the recently arrived converso refugees, this opened up the possibility of building a new life for themselves in a land of unbridled opportunity.

The Dutch expedition landed in the port of Recife with an armada of 56 ships and 7,000 men. Their commander sent a message to the town saying that “the liberty of Spaniards, Portuguese, and natives, whether they be Roman Catholics or Jews, will be respected. No one will be permitted to molest them or subject them to inquiries in matters of conscience or in their private homes.”

Antonio Dias Paparrobolous travelled as a guide to Recife with the expedition. A converso, he had originally gone from Brazil to the Netherlands, where he had found his way back to Judaism. He was now returning to Brazil, to persuade his former converso friends and neighbours to do the same.

Steadily, the number of professing Jews in the colony rose. Some had been converted back to Judaism by Antonio Paparrobolous, others arrived from Spain, Portugal, Italy and, most of all, the Netherlands. By 1644, approximately 1,450 Jews were living in Recife, making up two fifths of the European population of the town. There were now as many Jews in Recife as in Amsterdam.

Recife’s Jews mainly worked in the sugar trade. Some bought the sugar mills abandoned by Portuguese who had fled after the Dutch invaded, others acted as sugar brokers or financiers. A number became tax farmers, collecting taxes on commission for the authorities. Several, shamefully, were involved in the slave trade, acting as middlemen between the slave importers and the plantation owners. The Jewish involvement in the slave trade has long been ignored or played down by historians and communities; it is only now, finally, being discussed.

As is so often the case, the commercial success of many Jewish families led to a backlash. Despite the official policy of religious tolerance the ruling body of the Dutch Reformed Church, the official religion of the colony, complained of Jews congregating publicly for worship in Recife. This, they said, disturbed the faithful of the Protestant Church and led Portuguese Catholics to assume that the Dutch were half-Jewish, since the Jews were permitted so many liberties.

As a result the government of the colony ordered the Jews to henceforth conduct their religious services in seclusion, in private houses, and to do so quietly, so as to not be heard by the Christian population. But the Jews, unsurprisingly, did not comply. In 1640 the Church’s ruling body complained that Jews had not only failed to obey this order, they had aggravated their offence by building a synagogue and taking out a lease on land for a cemetery.

The complaints against them do not appear to have bothered the Jewish community. For in 1642 they invited two rabbis to join them from Amsterdam. One, the Portuguese born Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, had been the first rabbi ever to be appointed in Amsterdam. That he agreed to leave a post of distinction for Brazil is an indication of the prestige (and presumably financial muscle) of the Recife community. He travelled to Recife with his colleague, Moses Raphael d’Aguilar, also from Amsterdam. The two men were the first rabbis to minister on the American continent; Aboab being appointed to the main synagogue in Recife, d’Aguilar preaching in the neighbouring congregation in Mauricia.

Things did not work out well for Recife’s Jewish community. Its brief life came to an end in 1654 when the Portuguese invaded the colony and seized possession from the Dutch. For those former conversos who had returned to Judaism, the return of the Catholic Portuguese threatened to be a disaster. They would be subject once more to the Inquisition, in whose eyes they were guilty of heresy. Their lives were in danger.

They had, however, seen it coming. For several years the Portuguese had been getting closer and the Dutch colony of Recife was growing increasingly isolated. Jews had already started to leave, most of them heading for Amsterdam. By the time the Portuguese arrived in the town there were only 600 left; very few of them former conversos.

The new Portuguese governor was not a hard man. He told them that nobody would be obliged to abandon their homes; if they chose to leave, he would give them three months to sell up and go. He would even make boats available for those who wished to sail elsewhere.

But there was little point in them remaining. The economy was in ruins and any Jews who stayed would almost certainly be obliged to accept baptism. Most of the 600 decided to go back to Amsterdam, the rest resolved to try their luck elsewhere in the Caribbean.

A total of 16 boats left Recife carrying Jewish exiles. One was intercepted by a Spanish frigate. The crew captured its Jewish passengers and made preparations to hand them over to the Inquisition, probably in return for a fat reward. In true buccaneering style they were saved by a passing French gunboat which rescued them and took them to Florida.

A second boat from Recife, allegedly carrying about three dozen Jews and a hundred Dutch Christians was also intercepted. Their fate was less happy. They were taken to Spanish Jamaica, where the Jews were handed over to the Inquisition. The Dutch government intervened and negotiated the release of 23 of the Jews; four men, six women and thirteen children. No record survives of what happened to the others, if indeed there were any others.

The 23 Jews were taken to Cuba where they eventually negotiated a passage to New Amsterdam. The captain of the boat who agreed to take them to New Amsterdam demanded an exorbitant fee, with one third payable up front, the rest on arrival. Six weeks later, when the boat reached New Amsterdam, it turned out that the passengers could not pay the balance of the fee. The captain seized their goods and tried to sell them at auction. When the sale failed to produce enough money, two of the Jews were thrown in jail, where they remained until money arrived from their relatives in the Netherlands.

Of the 1,450 members of the Recife Jewish community, the first in the Americas, only 23 now remained on the continent. They had lost everything. Forced to start again, to make a life for themselves in New Amsterdam, soon to be renamed New York, their endeavours are the start of another chapter in American Jewish history. But that is another, much longer, story.

Fascinating. I knew nothing about this history until recently when I discovered that many of my immediate family of that period were part of these communities.

Do you have lists of residents of the settlement in Recife & Suriname?

Thanks, I'm glad you found the article useful.

Take a look at Arnold Wiznitzer's book "The Records of the Earliest Jewish Community in the New World." There are no lists as such but plenty of names in the index. You can read it online at https://archive.org/details/recordsofearlies0000arno.

Wiznitzer was one of the very few historians of the Recife community, he wrote in the 1950s and mainly published his articles in the journal "Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society". So if you don't find what you are looking for in his book, try scouring his articles. You can access them all at jstor.org, just search for his name or that of the journal.

Good luck! And thanks so much for subscribing!