She was a legend; for the best part of a century no Jewish kitchen could be considered complete without her. For those of us growing up in post-war Britain, she was a fixture in our mothers’ and our grandmothers’ lives. We thought of her as old and venerable; it would not have been a surprise to us to hear that she had come out of Egypt with Moses. In fact she didn’t, she lived among us, in a small flat in Baker Street, in London’s West End.

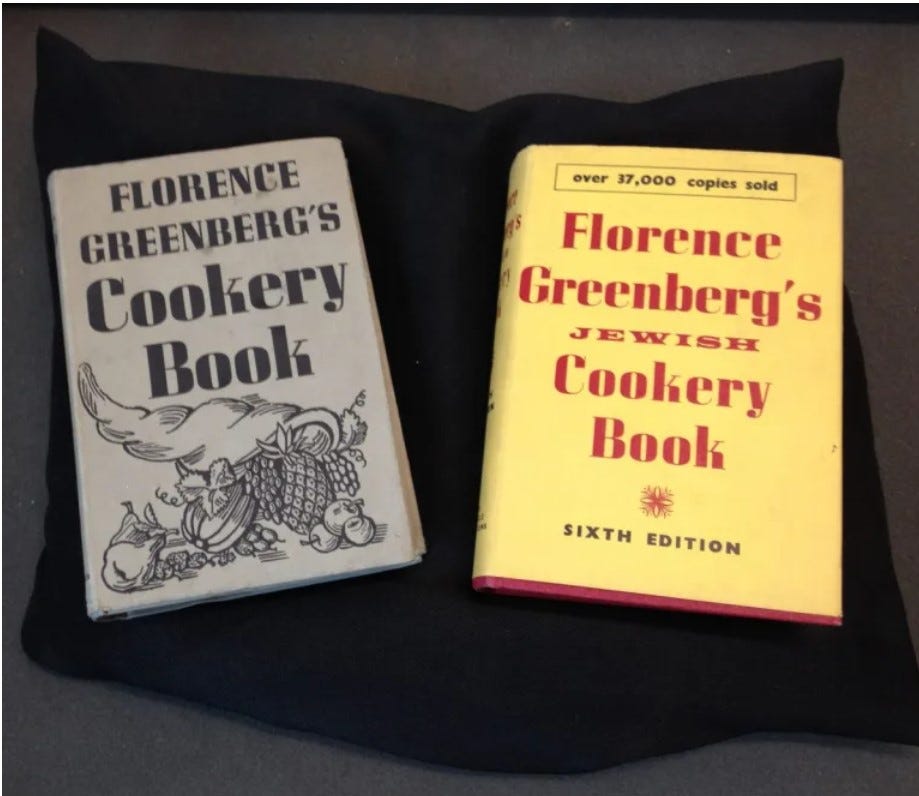

Florence Greenberg’s Cookery Book was the culinary bible for Britain’s Jews. It remains so for many. When the first edition came out, in 1934, there were far fewer cookbooks around than there are today. Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, first published in 1861, was still the cookbook of choice in many British households; Florence Greenberg was our Mrs Beeton, which might explain why we thought she was so old.

Florence Greenberg didn’t train as a cook and never intended to write a cookery book. But she had grown up in a large family, she was the fourth of eight children and for ten years she helped her mother run the household. She said that she got her cooking experience through trial and error.

Born as Florence Oppenheimer in North London in 1882 she had wanted to be a nurse but her father forbade it. He said it wasn’t appropriate for girls to ‘tamper with men’s naked bodies’. But by the time she was 29, fearing that if she waited any longer it would be too late, she persuaded her brother to have a word with their father. Her father gave way and she began training as a nurse at the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton. She qualified just as the First World War broke out and immediately enlisted as a reserve nurse.

In the summer of 1915 she was sent to Plymouth where she boarded a troop ship bound for the Eastern Front. She described the hot and cramped conditions in her diary, sharing a cabin with three other nurses: “The cabins are very small, there is just room for our holdalls underneath the berths, our cushions, bags and clothes have to live on the end of our berths when we are asleep and we can only dress two at a time.” Conditions became unbearable when they entered the warm waters of the Mediterranean, until it dawned on them to take their mattresses onto the deck and sleep in the open air.

While travelling, Florence spent a couple of days happily talking to a serious young medical officer. Eventually he proposed to her, which seemed to genuinely surprise her. “I wanted to laugh at him, however he really seemed in earnest, so I thought the best way out of the difficulty was to tell him my religion, in any case that hurt his feelings the least. I cannot think what made him do it, I certainly had not encouraged him at all.” He was Catholic. It sounds as if she was relieved he wasn’t Jewish.

At Gallipoli, Florence was transferred to a hospital ship, the Alauria. It was here that she was exposed to the full horrors of war. She described working on board a ship with 2,000 patients on board and only 10 doctors, with stretcher cases “simply pouring in.” Half the nursing staff were redeployed to another ship and Florence was just one of ten nurses left to tend to all the casualties. Her efforts earned her a Mention in Dispatches.

Florence Oppenheimer returned to London after five years services overseas. In 1920 she married Leopold Greenberg, the proprietor and editor of the Jewish Chronicle. Greenberg, a lifelong Zionist for whom the newspaper was his own personal fiefdom, had recently successfully waged a successful campaign against the entrenched leadership of the British Jewish community. Not wishing to be seen as having divided loyalties they had opposed the British government’s Balfour declaration promising a national Jewish homeland in Palestine. Greenberg’s campaign in the newspaper had ensured that Jewish public opinion supported the government and the Zionists. The British government expressed its gratitude to Greenberg by holding up publication of the Balfour declaration until it could first be announced in the pages of the Jewish Chronicle. According to David Cesarani z”l the government subsequently used Greenberg and the Jewish Chronicle in their propaganda (a situation not dissimilar to today, if you are familiar with the current structure of the Jewish Chronicle).

Leopold Greenberg suggested to Florence that she write a cookery column for the paper. When she protested that she had no literary skills he riposted: “‘What do you want literary ability for? You are a marvellous cook.’” After that, she said, she could not refuse. Florence Greenberg wrote a cookery column for the Jewish Chronicle for the next 42 years.

Leopold was considerably older than Florence when they married and he died in 1931 after they had been married for just eleven years. His son Ivan, from his first marriage, took over the editorship of the paper and asked Florence if she would compile her previous articles into a book. Other newspapers were publishing compilations of their cookery correspondents’ articles but Florence wanted something more than that. She could see the need for a Jewish Cookery Book, a heritage work that preserved her own creations together with traditional Jewish recipes and explanations on how to manage a kosher kitchen.

In 1934 the Jewish Chronicle Cookery Book was published. It sold for 3 shillings and sixpence, the equivalent of 17.5 pence today, or around 22 cents. 5,000 copies were sold and the newspaper decided to bring out a second edition. But before they could do so, their offices were destroyed by the Germans in the London Blitz and all her notes and records were destroyed. Nonplussed, Florence resolved to start again.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Food had heard of Florence and asked her if she would teach housewives how to make do with the meagre food rations available. They particularly wanted her to speak to Jewish groups, to explain how to subsist while keeping to the rules of kosher cookery. When she went for an interview at the ministry she expressed her reticence. “I explained that I wasn’t a lecturer, and really I couldn’t undertake it. [The interviewer] said ‘Mrs Greenberg, I haven’t been talking to you for the last half hour without realising that you are just the person we want, a practical housewife ‘to get it over from me to you.’” I felt I must do it after that, and I accepted the job.” For the rest of the war she travelled the country, carrying ingredients and samples to show Jewish evacuee families how they could get by on the limited supplies available.

Then the BBC took an interest in her. She began to broadcast on The Kitchen Front, a light hearted war-time information programme under the auspices of the Ministry of Food. The high point of the show was BBC announcer Freddie Grisewood’s role as ‘Man in the Kitchen’, instructing incompetent middle-class men on how to cook for themselves. Florence Greenberg’s contributions to the programme included instructions on Date Cake and Date Fillings, a Red Cabbage recipe, Vegetable Flans and Gingerbread Cake.

Meanwhile she had been working to recreate the Jewish Chronicle Cookery Book. Now called Florence Greenberg’s Jewish Cookery Book, it came out in 1946. Since then it has been through eight editions and sold over 120,000 copies. However, the most recent edition is not exclusively Florence Greenberg’s work. It has been ‘modernised’, to reflect contemporary styles of cooking, greater use of refrigeration and modern kitchen equipment (though the edition came out in 1980 so it is in quite some need of further updating itself).

Florence Greenberg’s Jewish Cookery Book is now one of thousands of cookbooks available to Jewish cooks. She has been joined at the pinnacle of the Jewish literary cooking canon in Britain by Evelyn Rose and Claudia Roden, with others no doubt joining them in due course. But Florence Greenberg will never be replaced. Like Mrs Beeton her culinary legacy is assured. She lived a long and much admired life, dying in 1980 at the age of 98, a few months after the updated edition of her cookbook was published. But the value of her book has not diminished. Who else can tell you how to make tzimmes, kreplach, kishkes, lockshen pudding or eingemachts the way your grandfather used to like them?