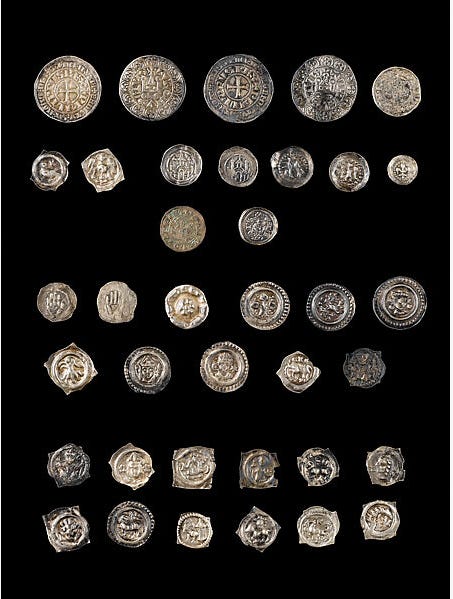

In 1863, a group of builders were working on a shop in the town of Colmar in France. They were hacking away at a wall in the Rue des Juifs, the old Street of the Jews. As they worked, they came across a pile of small dusty items in the wall. They saw some shiny flecks beneath the dust and carefully rubbed away at the grime. Pretty soon it was apparent they had unearthed a trove of old coins and jewellery, gold, silver and glass: rings, brooches, buttons, pins, keys, even a silver stylus for writing in a wax tablet.

Colmar is in the Alsace region of France, close to the border with Germany and Switzerland. Its history dates back at least to the 9th century and it still has a well-preserved, old town centre. The earliest mention of Jewish life in in the town is in a document dated 1278; Jews are described as living in their own quarter of town, they are said to have good relationships with the Christian population and they were a relatively large community (though large in those days probably meant no more than two or three hundred souls).

The next that is heard of Colmar’s Jews was just one year later, in 1279, when a fire destroyed the town’s synagogue. Whether the fire was due to foul play is not known but relationships between the Jews and Christians were probably already deteriorating because in 1285, when the town was besieged by enemy forces, the Jews were blamed and expelled. They were readmitted a few years later but were soon accused of ritual murder. A riot broke out and several were killed.

The Jews of Colmar were a mercantile community, they earned their living through pawnbroking or trade, buying and selling at local trade fairs, the site of most business transactions in the medieval age. Some Jews dealt in merchandise they had imported, or in cloths and skins, others took part in the wine industry, for which Colmar was an important centre. In that sense, the history of Colmar’s Jewish community seems very similar to any other; just another unremarkable town with a long history, sometimes peaceful, at other times their lives peppered with slaughter and expulsions. Yet the treasure found in the shop in the Rue des Juifs gives us a completely different perspective on the life of some Jews in those days.

For there is no doubt that the jewellery belonged to a Jewish family. The most remarkable piece in the collection is a wedding ring. Not simply a gold band, but a gold and enamel ring, on top of which is a small hexagonal dome, as illustrated above. Supported by four arches, the dome is supposed to evoke the long destroyed Temple in Jerusalem. Inscribed on the ring are the two Hebrew words, mazal tov, meaning ‘good fortune’. It is one of the earliest and most intricate pieces of Jewish jewellery to have survived. There is also an onyx ring reflecting an early superstition that the stone was a medium for communicating with the dead.

The wedding ring may not have been crafted in Colmar. The style is Italian. But the provenance is less important than the ring’s significance. Like all the jewellery found in Colmar it reminds us that, although long forgotten, medieval European Jewish art may have been far more plenteous than the illuminated manuscripts, prayer books, bibles and haggadot that are regularly exhibited in museums, or the silver Torah ornaments and spice boxes regularly displayed. Jewish artists were not unusual in Muslim lands or even in Italy. But they are virtually invisible in medieval Europe. It is hard to know how many people worked as goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers in such communities, because their output has not survived. Precious metals are easily melted down for easier transport or concealment during times of crisis. Left as ornate jewellery, they would have been much more susceptible to theft or confiscation.

It is also hard to know how many families were prosperous enough to own the sort of jewellery found in Colmar. A much larger hoard, dating from exactly the same time, was found in the German city of Erfurt in 1998, as have several troves hidden during the crusades. Nevertheless, they are few and far between; hardly evidence of a flourishing wealthy class. It is undoubtedly the case however that the few hoards which have been found were hidden by people in fear of their life or intending to flee, hoping to keep their possessions safe in case they were fortunate enough to survive or return.

In 1348, the Black Death, or bubonic plague, swept through Europe. It was devastating. Up to half of Europe’s population died, perhaps as many as 50 million people. The primitive medicine in those days was sufficient to recognise that the plague was contagious, but not sophisticated enough to understand how the infection was transmitted. Instead, the Jews were blamed. Rumours began circulating that Jews had been poisoning the wells and streams and that the infection was spreading through the drinking water.

A late 14th century German history contains the report of a ‘confession’ made by a Jewish man named Agimet, at Chatel in Switzerland. After having twice been ‘put to the torture a little’, Agimet allegedly told his persecutors that he had recently travelled to Venice. A rabbi had sent for him as he was travelling and given him some ‘prepared poison and venom in a thin, sewn leather bag’. The rabbi had told him to place the poison in Venice’s wells. Agimet had done as he was told and had also placed some of the poison into wells in Calabria, Apulia, in the city of Ballet and in the public fountain of Toulouse. A little poison, it seems, goes a long, long way. Particularly if spiced with torture.

Colmar suffered from the plague as badly as anywhere. And, like everywhere, they blamed the town’s Jews. On 29th December 1348, the city council sent a message to their colleagues in Strasbourg. They told them that they had arrested a Jew named Hegman who, after being tortured, had told them that Jacob, the cantor of the synagogue, had sent him the poison that he had put into the city’s wells.

As soon as the people of Colmar heard of Hegman’s alleged confession, they attacked the Jews, those who had not already fled. There was no hearing, no trial. All the Jews remaining in the city were driven through the gates of the city to a huge pyre that had been built. They may have been offered the option of conversion to save their lives; some of the children may have been torn from their parents, baptised and taken into Christian families. Everybody else was burned to death. There is no record of survivors.

So we come back to whoever it was who hid the treasure in the wall of the old shop on the Jews’ Road. They must have had some sense of what was about to happen, there must have been some planning involved in building a hiding place that would survive for 500 years. Nobody knows who the family was, the only thing known about them is that they never returned to their home to collect their possessions. In one form or another it is a story that’s sadly all too familiar.

Thank you for this. I am fascinated by the artistic and technical skills that people had so long ago, without any of the tools and machinery we take for granted.

Thank you for the beautiful contribution. Incidentally, almost everything you wrote also applies to the Jewish community in Erfurt, which was completely wiped out on March 21, 1349. Up to 900 people died.

The Erfurt wedding ring is even more delicate. The underside of the broad ring is decorated with the motif of clasped hands, an ancient symbol of marital fidelity. On the sides of the ring, two winged dragons carry the finely wrought Gothic temple architecture. The inscription “masel tow” is also engraved in six Hebrew letters on the smooth surfaces of the roof.

https://juedisches-leben.erfurt.de/jl/de/mittelalter/erfurter_schatz/fundstuecke/index.html