In an article in the New York Times just before the 2016 election, Professor Stephen Greenblatt, the doyen of Shakespearean and Renaissance scholars wrote: ‘Shakespeare’s words have an uncanny ability to reach out beyond their original time and place and speak directly to us’.

The only other work of world literature that shares Shakespeare's ‘uncanny knack’ is the Bible. One of the Bible’s great qualities is that although it is a religious text it can also be read as secular literature, particularly the narrative sections. Unfortunately because it is the foundation of Western monotheism, and religion is unfashionable these days, the Bible is disregarded as a literary trove. But if we put religion on one side and think about some of the secular ideas it contains, we soon remember that when it comes to speaking directly to us, the Bible, just like Shakespeare, is unparalleled.

Genesis, the first book in the Bible, deals with many secular subjects. War, tribalism, patriarchy, territorial disputes to name just a few. But the subject it returns to more often than any other is sibling rivalry. At no point does the book tell us that it intends to discuss the subject, but from the way it narrates stories about siblings there is no doubt that it has a view, and an agenda.

The first siblings in Genesis are Cain and Abel. Born into an empty world, they quarrel. We are not even told what it the quarrel is about, it hardly matters, but it ends with Cain killing Abel. It is extreme of course, siblings don’t usually kill each other, but which child has never felt so enraged towards their brother or sister that their passions, if only fleetingly, cloud their judgement? And look how Cain reacts after the murder, when he is asked where Abel is. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Like a petulant child he shrugs off his crime. “What’s it got to do with me” he sulks, “leave me alone?”

Ishmael and Isaac have a more complicated relationship. They are the children of a prosperous household. Ishmael is the elder but as the son of the concubine Hagar he knows he will never have the same status in the family as Isaac, born to Abraham’s first wife Sarah. Ishmael was thirteen years old when Isaac was born, old enough to resent the newcomer and make fun of him. Their real issue though is the relationship between their mothers: Sarah resents Hagar, she cannot live in the same house as her. However, out of all the sibling pairs in Genesis, Ishmael and Isaac seem to have the best relationship. They can’t live together, but nor is there is any sign of hostility. They come together at the end to bury their father.

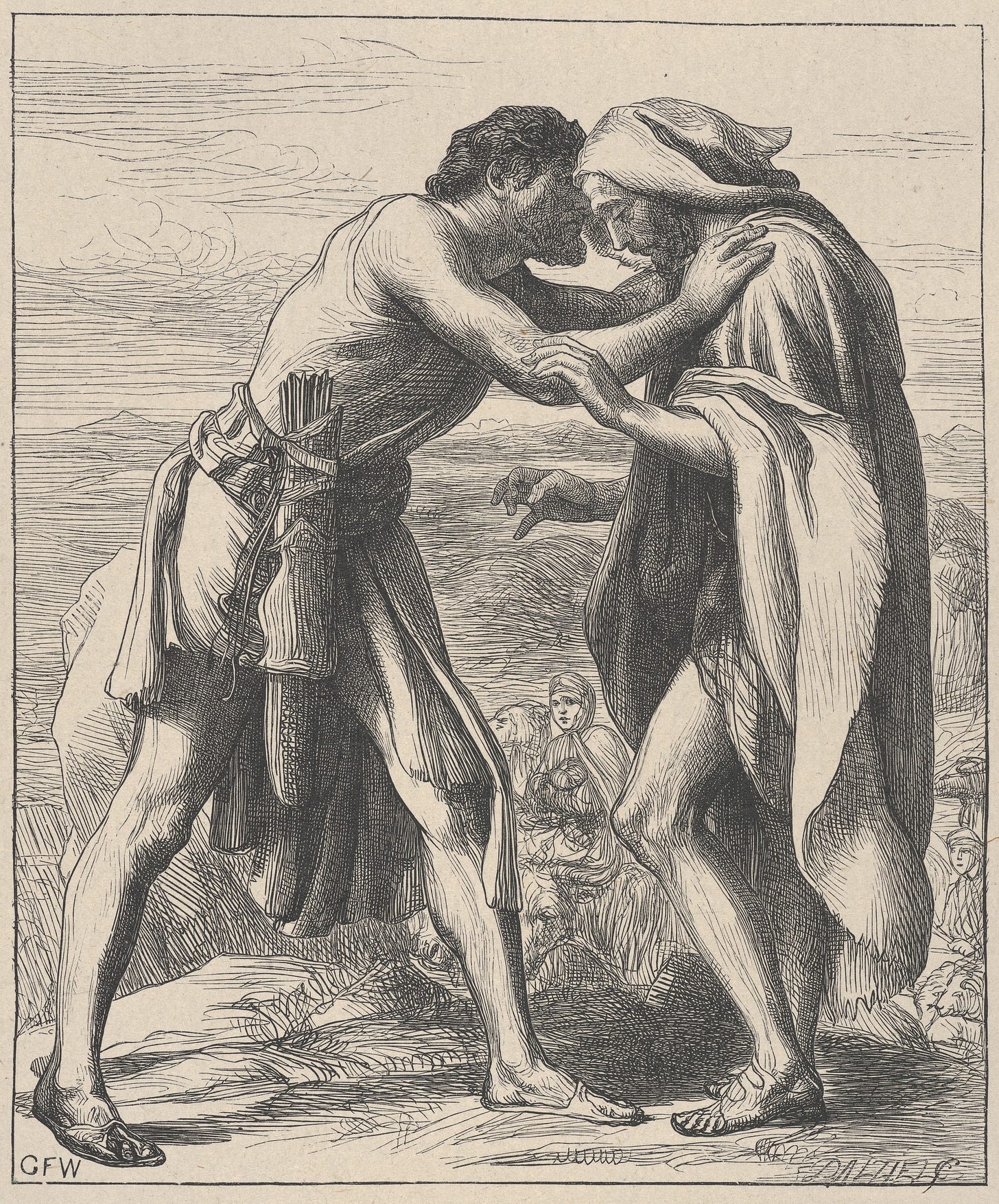

Things take a turn for the worse with Jacob and Esau. The family is completely dysfunctional. Isaac loves one child and Rebecca the other. Esau, the first born twin, his father’s favourite, is born with his brother hanging onto his heel, their rivalry commencing even before they draw a breath. Jacob, Rebecca’s favourite, resents being cast into the role of a mummy’s boy, he is jealous of the privileges afforded to Esau by virtue of being born a few moments earlier. Meanwhile Esau, deprived of his mother’s love, brought up with only his farther as a role model, retreats into self-sufficient, passive aggressive isolation. The rivalry between the twins never heals, becoming enmity when Rebecca encourages Jacob to deceive their father, at Esau’s expense. When Esau vows to kill Jacob we do not hear the voice of a petulant Cain. He is deadly serious. There is no happy ending for this damaged family.

Finally we have Joseph and his brothers. Twelve boys and a girl, born to four mothers, two of whom are sisterly rivals themselves, all living in the same household. All children of Jacob whose own experience of childhood was growing up in a dysfunctional family. It is a recipe for disaster. Jacob makes the same mistakes as his parents but exaggerated twelvefold because he has so many kids. He prefers Joseph over all his other children, treats him as the special one. Matters are made worse by Joseph’s narcissism; he dreams that he is superior to his brothers. No wonder his siblings (with the exception of his sister Dinah) conspire to take their revenge. When Joseph does attain a position of power, making him believe his dreams have come true, he makes sure he gets his own back over his brothers. Eventually, there is some sort of reconciliation. But only because Joseph’s brothers lie to him about their father’s dying words. Of all sibling rivalries in Genesis, this is far and away the worse. It is also, historically, the most consequential, leading directly to the slavery in Egypt and the Exodus.

What is Genesis telling us? We have to deduce it because there is no hint in the narrative that sibling rivalry is on its mind. It does seem from the matter of fact way in which the stories are told that Genesis regards sibling rivalry as natural and unavoidable. Each set of siblings is left to deal with their particular problems in their own way, there is no divine hand helping them out. Unlike Shakespeare, whose treatment of sibling rivalry in King Lear is condemnatory, Genesis’s ultimate message seems to be that family problems are unavoidable. There is a message for the parents, don’t favour one child over another. But as far as the siblings are concerned, the moral is: deal with it; it’s what happens in life.

One thing stands out very clearly though. Not just in Genesis but throughout the Bible. Whenever there is rivalry between siblings it is the younger who comes off best. The eldest invariably fails or ends up playing second fiddle. If we put the religious mantle on for just one moment, we might be reminded of God’s declaration in Exodus that Israel is his first born son. How’s that for scary?

Sibling rivalry has consequences. The siblings in Genesis seem to get over it, apart from poor old Abel. But it is disastrous in King Lear. And in post biblical Israelite history, there are real consequences. Last week I mentioned two brothers Aristobulus and Hyrcanus who lived in the 1st century BCE. They were sons of Alexandra Salome, a queen of Israel also known as Shlomzion. She was a pivotal figure who deserves far more attention than she gets these days. Her husband Alexander Janneus had been both king and High Priest and when he died she claimed the throne. As a woman she couldn’t become High Priest (we might ask why), so she appointed her son Hyrcanus to the position. The historian Josephus said she chose him because he delighted in a quiet life and chose not to meddle in politics. She knew he wouldn’t cause her any trouble.

Alexandra was a tyrannical queen. Calling her mad with ambition, her younger son Aristobulus, who was peeved at the favour she had shown towards his brother, bided his time. When she grew ill he made his move. Civil war broke out between the brothers. Aristobulus was by far the stronger. If there had been no interference victory would probably be his.

But neighbouring Syria was Roman territory. The Romans, watching what was happening on their borders, grew increasingly anxious. They could see that the Israelite nation was disturbingly volatile and that both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus were hated by the masses. Political insecurity in a disputatious nation right alongside them was more than the Roman general Pompey was willing to stomach. He didn’t want the subjected Syrian masses getting ideas. In 63 BCE he intervened, besieging and eventually capturing Jerusalem.

Pompey’s capture of Jerusalem put an end to the civil war between the brothers and restored stability to the region. But the hitherto independent Hebrew nation was now under Roman control. The world would never be the same again. The Roman occupation of Israel led directly to a series of world shaking events, most notably the crucifixion of Jesus and the destruction of the Temple.

Pompey’s intervention in a dispute between two brothers set the course for over 2,000 years of world history, probably more. That’s what sibling rivalry can do. Good thing, or bad thing? You tell me.