A few weeks ago I published an article on Jewish doctors and asked whether you would like to read more pieces on the subject. The response was overwhelmingly positive, so I am writing about doctors again this week.

I am not able to write much about the doctor I would most like to discuss. She was not the first Jewish woman doctor in history, but she was among the most highly regarded, counting royalty among her patients. Her name was Floreta Ça-Noga. She lived in Santa Coloma de Queralt, about 100 km west of Barcelona and on 20th January 1374 she was granted a licence by King Peter IV of Aragon to practise medicine throughout his territories. The licence describes her as “fit and sufficient in the art of medicine” and praises her diligence and lengthy experience as a medical practitioner.

Floreta must have been a practitioner of some distinction. Court records show that she looked after Queen Eleanor of Sicily, the wife of King Peter IV of Aragon and, after her death, Queen Sibilla de Fortià. The records also show that she was paid more than was customary.

Unfortunately, nothing else is known about Floreta, nor indeed about any of the women doctors who lived during the Middle Ages. Only a few names remain, like Bellayne, the widow of Samuel Gallipapa, and her daughter-in-law Na Pla, who were both licensed in Zaragosa, in 1380 and 1387 respectively.

Interaction between Jews and Christians was severely restricted in the medieval world and Jewish religious laws about impropriety limited contact between men and women. Doctors bent the rules and few minded; Jewish women doctors treated men as well as women, Christians as well as Jews.

This did cause some concern when Hava, a Jewish woman, was called to treat a Christian man who had been wounded in the genitals. A court asked her what she had done. She told them that she had taken her son with her, that she merely gave instructions and that the boy had carried out the treatment.

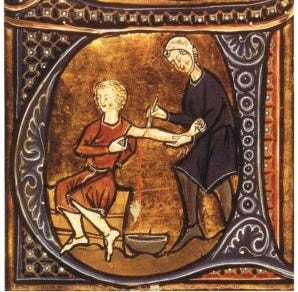

Like Jewish men, medieval Jewish women had no opportunity to study medicine at a university. Nevertheless, they were trained; the fact that they were licensed meant that they were not just run-of-the-mill healers, who used folk remedies, incantations and a good deal of wishful thinking. To be trained and licensed as a doctor gave them official sanction for their work, and the ability to charge more for their services. And to obtain a licence they not only had to provide evidence of their skills, they had to be aware of the early medical theories of the Greek physician Galen and the later Arab doctors who had built upon his ideas.

The only way women could train to become doctors in those days was by living and studying with other physicians. In most cases they would have trained with a man; history has preserved the name of just one woman doctor who is known to have trained others. Her name was Sara de Sancto Aegidi, of Marseille. She entered into an agreement in 1326 with her pupil, Salvetus de Burgonoro. She would teach him ‘the art of medicine and physic’ for a period of seven months, he would board with her during that time and she would provide his food and clothing. He, in turn, would hand over to her, all the fees that he earned while training.

Salvetus’s name suggests that he was a Christian. His close relationship with his Jewish teacher is just another example of how little is really understood about interactions between Jews and Christians on a personal level, in an age when Jewish communities were frequently under attack or being uprooted.

One of the few studies of early Jewish women doctors was carried out by the Baltimore ophthalmologist, Dr Harry Friedenwald. His 2-volume work, Jews and Medicine was first published in 1944. Among the many doctors he describes is the woman who treated the 13th century German rabbi, Judah ben Asher. The son of Asher ben Yehiel, one of the foremost Talmudists of the medieval period, Judah was never able to reach the same scholarly heights as his father because he was partially blind. His ability to read and study at all was, he explained, due to the Jewish eye doctor who treated him (unfortunately he did not think it important to record her name):

When I was three months old I suffered with my eyes and did not get better.... a woman endeavoured to cure me but she increased my blindness so that I was confined to the house for one year because I could not see . . . until a Jewish woman skilled in the healing of the eyes came. She treated me for two months but then she died. Had she lived another month, I might have regained my eyesight fully. Were it not for the two months she treated me, I might never have seen any more.

Germany, and Frankfurt in particular, was especially well-endowed with Jewish women physicians. The first recorded name to have survived, was of a woman named Selekeid who was practising in 1393. But again, their names are all that is remembered about the Frankfurt doctors. There is no information anywhere about their lives or their medical activities. Apart from their dealings with the tax authorities. The Frankfurt treasury was good at keeping tax records.

There must have been some sort of tax exemption for doctors in Frankfurt, but it evidently wasn’t consistent. In 1439, women doctors were ordered to pay the same tax as all other Jews, suggesting they were not doing so before. If they didn’t pay they were ordered to leave the city. But there were exceptions. One doctor, who was treating the toll-master of the bridge was excused from paying any tax at all, and in 1457 a woman doctor who had been ordered to leave the city because she hadn’t paid her taxes, was offered a discount if she would only consent to stay. The city agreed to tax her at the same lower rate that rabbis and cantors paid. Some years later, when an outbreak of plague highlighted the shortage of doctors in Frankfurt, a Jewish woman who visiting Frankfurt was excused from paying the ‘strangers’ tax’. They needed her to help deal with the disease.

For many women, their skills at medicine cancelled out the disadvantages they suffered under as Jews. Sarah of Würzburg was given a licence by the local archbishop to practise medicine throughout his lands. She had to pay ten florins a year for the privilege but in return the archbishop guaranteed that she may practise her profession without interference: “And should anyone intend to prosecute her or actually do so, against such one we shall take action to the best of our ability so that he be stopped, unconditionally.”

Sarah must have been a particularly successful doctor because the local prince, Friedrich von Riedern, issued a decree granting her the usufruct, or right to benefit, from all his possessions, throughout the Duchy of Franconia.

It goes without saying that women Jewish doctors, just like their male colleagues, were often the target of abuse. When the Jews of Trent were massacred in a blood libel, after the death of a young child, the Catholic priest Bernadino of Siena accused Brunetta, a female Jewish physician, of supplying needles to draw off his blood. A 14th century Swiss poet complained about Christians ‘who are so foolish, that. . . they call in a Jew or a Jewess who practices medicine . . . even though there is a Christian physician in their midst.’

It is a shame that so little information has survived about Jewish women who practised as doctors in the Middle Ages. It would be instructive and enjoyable to know more. Although a few rose to prominence, like Floreta, Sarah of Würzburg and Manuela of Rome who was the Pope’s personal physician, the great majority carried out their work quietly and invisibly, as was so often the lot of medieval women.

Even when Jews began writing medical textbooks in the 15th century there were no women among them. But the text books themselves, and their authors, are another story. I hope to write more about them shortly.

What an excellent post!