In 1807, Napoleon convened a Council of Jewish leaders and scholars in Paris. He did so to ensure that the Jews of France were religiously obliged to adhere to the laws and practices of his Empire. He called the Council a Sanhedrin; it was the first time the name had been used for at least 1700 years. Yet, despite its name Napoleon’s Sanhedrin was merely a shadow of what its forerunner was believed to have been.

According to the Mishnah, the Jewish legal code compiled around 230 CE, and later discussions in the Talmud, the Sanhedrin had been the Supreme Court and highest law–making body in ancient Israel. It had operated during the period of the Second Temple, perhaps from as early as 515 BCE to 70 CE. Composed of 71 judges, it sat in the Temple precincts and was the only court empowered to try capital cases. When the Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 CE, the Talmud implies that the Sanhedrin came to an end.

However, the Talmud was composed long after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple and the alleged demise of the Sanhedrin. There are no records from Temple times which offer any detail about the Sanhedrin or how it operated. Historians today are divided over what Sanhedrin actually was, its importance and indeed, for some, whether it in fact existed. Most historians now think that the description of the Sanhedrin in the Talmud was an idealised picture of an institution that the Talmud’s authors had heard of, but knew little about.

The only contemporary evidence that exists about the Sanhedrin is in the writings of the 1st century Jewish historian Josephus, and in the Christian Bible. Josephus writes about local civic assemblies with Greek names, gerousia and boulē, but he says virtually nothing about them. He also writes about a Roman governor who split the country into five separate regions, placing a Sanhedrin at the head of each.

Apart from that, all he does is to tell us a story. It is about the young Herod, the man who became the villainous puppet–king of Roman–occupied Israel. Josephus says that Herod was accused of murdering a local brigand and summoned to appear before one of the five Sanhedrins. True to form, Herod, who at the time was the governor of Galilee, turned up at the hearing with his personal army, terrifying the Sanhedrin into silence.

The only information we get from that story is that this particular Sanhedrin was used to try criminal cases. Not that it did them much good. Only one member of the Sanhedrin, a man named Sameas, was bold enough to stand up to Herod. He warned his colleagues that one day Herod would rise to power and take his revenge on them. His prophecy came true some years later; Herod became king and slew them all. Apart from Sameas.

Josephus’s portrayal of the Sanhedrin as a criminal court is echoed in the Christian Bible. The Gospels record that when Jesus was arrested he was brought in front of a Sanhedrin made up of priests and Pharisees (the forerunners of the Rabbis). The Book of Acts also mentions the Sanhedrin frequently, calling it the senate of the children of Israel. It states that Gamaliel the Pharisee, known in rabbinic literature as Rabban Gamaliel the Elder, was a member of the Sanhedrin.

These few references allow historians to conclude that something called a Sanhedrin existed, though they are not sufficient to describe it in detail. Nevertheless, when Napoleon decided to create a lawmaking council for his Jewish subjects he called it a Sanhedrin, following the reference in Acts to the Israelites’ senate.

Napoleon’s Sanhedrin was the culmination of a process he had begun over a year earlier. The French Revolution had granted full civil rights to the Jews but the process of integrating Europe’s long ostracised Jewish communities into civil society was more complex than decrees alone could solve. The centuries’ long prohibition against Jews entering the professions and craft guilds, and the church’s ban on Christians lending money on interest, had obliged many Jews to to earn a living through pawnbroking and money lending. This often led to bad relations with Christian neighbours; on top of all the usual antisemitic calumnies of well poisoning, blood libels and devilry, Jews were also vilified as usurers.

Napoleon, who wanted to subject all religions in his empire to government authority, had already reached an agreement with the Pope and the Protestants. He had not done so with the Jews because unlike the Christian denominations, Jews had no central authority for him to deal with. When he received reports in 1806 of unrest among farmers in the north of France who were accusing the Jews of usury, he took it as an opportunity to investigate the structure of Jewish communal life and its relation to the government. He wrote to his Council of State, telling them what he wanted:

According to an account given to us, in several northern departments of the empire, certain Jews, whose only profession is that of usury, have, by the accumulation of the most immodest interest, put many farmers in these lands in a state of the greatest distress…. On the 15th of July, in our fine town of Paris, an assembly of individuals professing the Jewish religion and living in French territory shall be created… The members of this assembly shall be … selected from amongst the Rabbis, the house owners and other Jews distinguished by their probity and their enlightened nature.

Napoleon told his Council of State that this assembly was to answer 12 questions, intended to ensure that Jewish religious practices conformed to French law. Looking a little like the sort of test that might have made your heart sink when you were at school, the questions were:

1. Is it lawful for Jews to marry more than one wife?

2. Is divorce permitted by the Jewish religion?

3. Can a Jewish woman marry a Christian, or a Christian woman a Jew? Or does the law only allow Jews to marry amongst themselves?

4. Do Jews regard Frenchmen as brethren or strangers?

5. What duties does their law prescribe to Jews towards Frenchmen who are not of the Jewish religion?

6. Do Jews who were born in France, and who have the legal status of French citizens, regard France as their fatherland? Is it their duty to defend it, to obey its laws, and to accommodate themselves to all the provisions of the Civil Code?

7. Who nominates Rabbis?

8. What police jurisdiction do the Rabbis exercise over the Jews? What kind of police magistracy do they recognise among themselves?

9. Are the forms of election and jurisdiction of the police magistrates laid down by the Jewish law, or merely consecrated by custom?

10. Are there any professions prohibited by Jewish law?

11. Does the law forbid Jews to practise usury in dealing with their brethren?

12. Does it forbid or does it allow them to practice usury in dealing with strangers?

The delegates to the new Assembly of Jewish Notables met in full sessions and sub–committees over the course of the next year. Their challenge was to respond to Napoleon’s questions in a way that would demonstrate their unswerving obedience to the laws of the Empire, while at the same time ensuring that they were not in conflict with Jewish law. The question that gave them the biggest headache was whether intermarriage of Jews with Christians was permitted. The progressives in the Assembly said that it was, the conservatives said no. In the end they came up with a formula saying that intermarriage was permitted, but that it had no validity in the Jewish religion.

As the Assembly concluded its deliberations, the delegates were told that the Emperor was satisfied with their answers and that he would summon a Great Sanhedrin to turn the answers into decisions and make them binding under Jewish law.

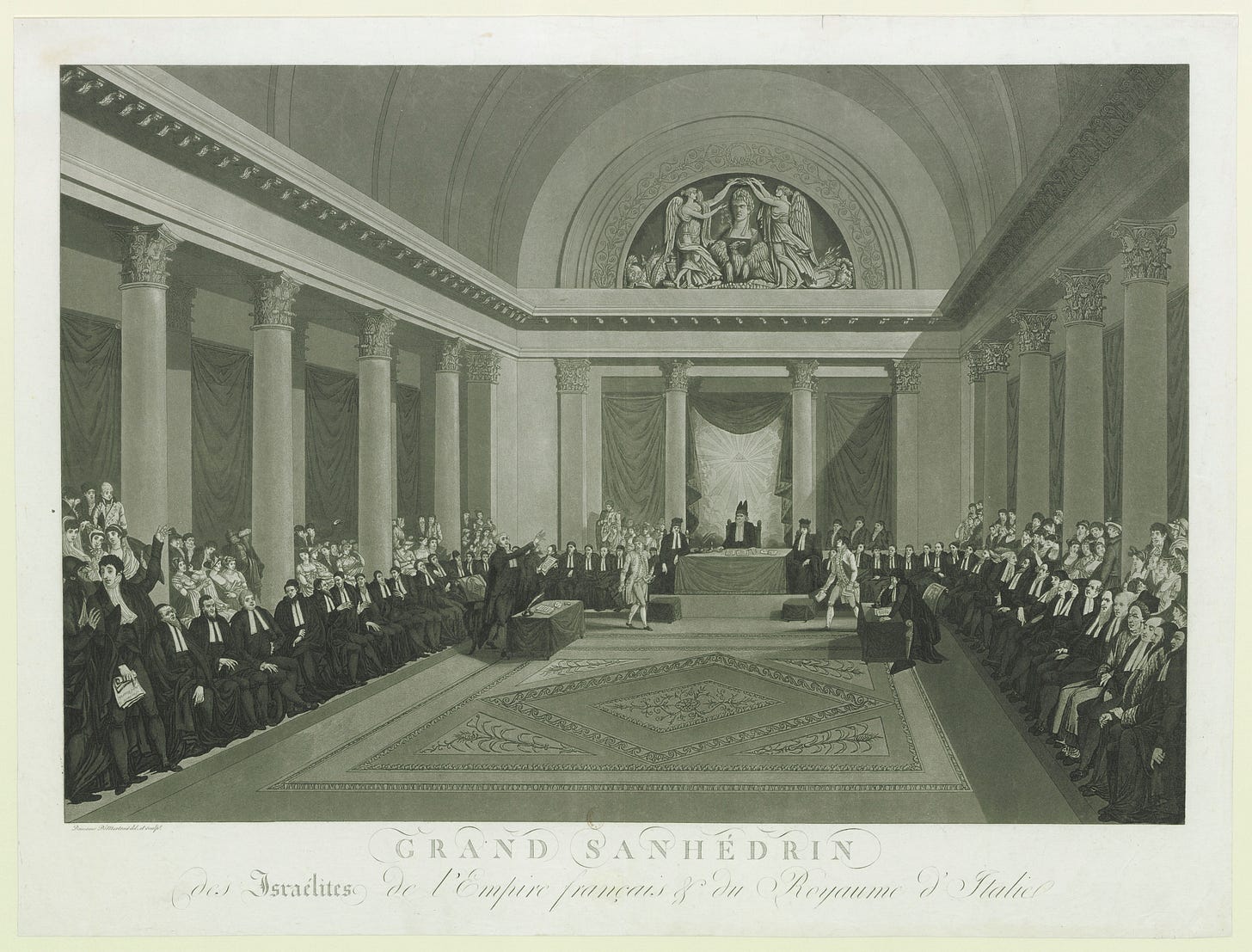

The Assembly was to invite Jewish communities across Europe to nominate delegates to the Sanhedrin. To replicate the sanctity that they believed had been attached to the Sanhedrin in former times, there were to be the same number of members of the Sanhedrin, 71 in all, of whom two thirds were to be rabbis and the remainder lay people. They were to sit in rows arranged in a semicircle, all wearing black robes, just as it was believed the ancient Sanhedrin had done.

Napoleon wrote to his Interior Minister telling him that the Sanhedrin needed to divide Jewish law into two parts. One part which could not be changed was the religious regulations, the precepts of Judaism. In the other part were the civil or political laws, all of which needed to meet with government approval. Questions such as polygamy, for example, were to be treated as political, rather than religious. Up to now it had been a religious custom for Jews not to practice polygamy; now the Sanhedrin was instructed to institute it as a binding, political law.

The Sanhedrin was convened in a solemn, formal ceremony in February 1807. They met eight times over the course of the next couple of months, under the leadership of the Rabbi of Strasbourg, David Sinzheim. The Sanhedrin condensed the Assembly of Notables’ answers to the 12 questions into 9 legally binding regulations and established a central governing body for French Jewry, the Consistoire, which took responsibility for Jewish life across the Empire.

By the time they had finished, it looked very much as if Napoleon had come up with the answer that had been bothering Jews ever since the beginning of the Enlightenment; of how Jews could become full and loyal citizens of the state in which they lived, while still retaining their distinctive identity. In many ways Napoleon’s Sanhedrin created the model that still operates in diaspora Jewish communities today, religious independence coupled with law–abiding participation in civic life.

Unfortunately, Napoleon was too much of an autocrat to see his project through. Despite the Sanhedrin’s conclusions, in March 1808 he issued a decree limiting the legal rights of Jews in his Empire. The Sanhedrin had come up with a proposal that met all his stated needs. He just didn’t have the democratic will to let them make it their own.

Harry, you always write about the most interesting little snapshots into history. I'm Latter-day Saint (AKA "Mormon"), and that list of questions gave me a visceral reaction. There's something about being in a religious minority that puts an immense amount of psychic pressure on you to perform when sources of authority put you under the microscope. (I've been asked if Mormons vote, and struggled to decide if it was a trick question of some sort...)

Ultimately, what was it that made him issue that decree in 1808? It sounds like they were full-steam-ahead on a democratic approach to a government that included the Jews, but to no avail.