Late to the Enlightenment

The Ongoing Impact of the Haskalah

In his recent book, The End of Enlightenment, Richard Whatmore hardly makes any mention of Jews. He has no reason to. However, in the very last paragraph he writes:

One of the remarkable facts about the post 1945 period was a renaissance of research concerned with the 18th century. Some of the greatest scholars were Jewish — the list is long but includes Isaiah Berlin, Peter Gay, Judith Shklar, Frank E. Manuel, Ralph A. Leigh and Theodore Besterman. Many had miraculously survived the Holocaust and all lost friends and family to the fascist genocide. Rather than turning against European history, they sought lessons for the present in the history of fanaticism and the strategies of enlightenment that were formulated to prevent it. We need to follow them and battle for enlightenment anew.

Whatmore contends that the 18th century cultural and intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment was a response to the religious wars that had plagued Europe for the previous couple of centuries. Philosophers like David Hume argued that these wars were the consequence of religious superstition and fanaticism, and that the solution to Europe’s problems lay in reason, tolerance and liberty. The idea of the Enlightenment laid the foundations for the democratic, secular world we live in today.

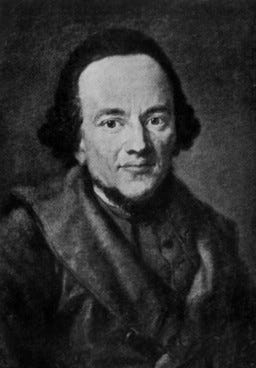

Jews were late to the Enlightenment. Living in ghettos and shtetls, and still recovering from the upheavals of the previous century, when the false Messiah, Shabbetai Tzvi, tore the Jewish world apart, they were largely cut off from the intellectual debates of the early and mid-18th century. The wars of religion had affected them just as they had affected everyone else in Europe but, played out between Catholics and Protestants, the issues at stake were of no consequence to them.

When Jews did finally pay attention to the new ideas that were circulating, the matters that concerned them were not those of political and cultural change in Europe. Rather, the advocates of the Jewish Enlightenment sought ways to rid Europe’s Jews of a mindset they considered medieval, to take them out of the ghetto and bring them instead into contact with the modern world.