In 1492 King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain expelled their Jewish subjects from their land. Many fled to the ports, desperate to cross the Mediterranean, to seek out new lives for themselves in lands they had scarcely heard of. The vessels they crowded onto were often unseaworthy, captained by men hoping to profit from the misery of the refugees, crewed by those hoping to extort what they could. Many of the exiles were murdered for their possessions before they were even able to set foot on the boats. Some managed to set sail, only to be sold into slavery on the north coast of Africa. Others were driven by the winds back to Spain and many drowned in the sea. Only a proportion of the refugees survived.

Those who did survive the fled to towns and communities across the Mediterranean. Some headed to the Ottoman Empire, where they would be relatively free to practice their religion and to live free of the persecutions and expulsions they had endured in Christian Europe. Some settled in Italy. One who did was Don Isaac Abarbanel (‘Don’ is a title, not a name).

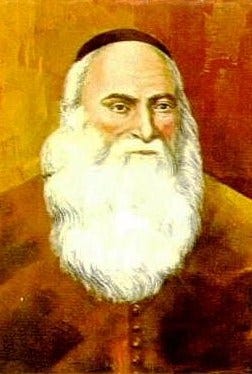

As far as historical Jewish personalities go, Don Isaac Abarbanel (or Abravanel, scholars and experts cannot agree how he pronounced his name) is one of the best known. He's not quite up there with the greats- he’s no Maimonides, Rashi or Saadia Gaon. But he’s not far behind.

Don Isaac is well known in Jewish circles today for his biblical commentaries and his works of humanist philosophy, but his reputation in the late 15th century was for financial acumen and diplomacy. He was born into a wealthy, aristocratic Jewish family in Portugal, and followed his father into the Portuguese royal court where he acted as one of King Alfonso V’s principal financiers. He was the principal contributor to a loan of 12 million reals raised on behalf of the king. When the Portuguese army conquered the African city of Arzila he negotiated and paid a substantial ransom to free 220 Jews who had been taken captive, about to be sold into slavery.

But when King Alfonso died, Abarbanel was accused of involvement in a conspiracy against the new monarch, Joao II. Sentenced to death, and with much of his wealth confiscated, he fled across the border to Spain. He set himself up as a tax farmer - collecting taxes on commission - and won contracts to supply the Spanish army. He became fabulously wealthy again, and ended up once more as a financier to royalty, this time to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. He helped to pay for their conquest of Granada and for the forced conversion they imposed upon the Muslim population. So immersed was he in the Spanish court that he was taken completely by surprise a few months later when the king and queen announced that all Jews in their kingdom were to be expelled. Abarbanel did his best, trying three times to first petition and bribe the king, but to no avail. He and his family were expelled from Spain with their fellow Jews, sailing on the same dangerous and unseaworthy vessels, sharing the indignities they suffered, until they disembarked as refugees on foreign shores. In Abarbanel’s case the foreign shore was Naples.

Abarbanel was one of the first Jewish bible commentators to try to make the text relevant to the lives of his readers. His commentaries examine the historical and literary aspects of the bible; unlike his predecessors he discusses complete narrative units rather than individual words and sentences. Occasionally he writes about himself. He described the experience of being driven from Spain in his commentary on the biblical Book of Kings:

On one day 300,000 enfeebled people, young and old, children and women, myself among them, departed from all the king’s domains, going wherever the wind would take them… Some went to the nearby kingdoms of Portugal and Navarre… Some made their way by sea, ‘a pathway in the mighty waters’. Yet even the hand of God was against them, to confound and destroy them. For many of the wretches were sold as slaves in foreign lands and many drowned in the sea, sinking like lead in the powerful currents. And some were cast into both fire and water, for the ships caught alight…

I chose the way of those who went by sea, and I am in exile. I came with my household… here to the praiseworthy city of Naples whose kings are kings of righteousness.

We should take the figure of 300,000 refugees with a grain of salt, but the rest of his description tallies with accounts from other contemporary sources. Of course, these days Abarbanel’s story would have been different. Supremely wealthy exiles do not flee along with the masses into death-trap boats on the Mediterranean. They climb onto private jets and continue their charmed lives elsewhere in the world.

Down and out in Naples was not the end of Don Isaac Abarbanel’s story. He remade his fortune once again and became a trusted associate of the city’s King Ferrante. When Naples fell to the French he fled with the royal court to Messina in Sicily. From there he went to Corfu and then to Monopoli in Apulia. As he journeyed he found time to complete his commentaries on the books of the Bible, and to compose several theological and philosophical tracts. Even in flight, Abarbanel was rarely idle.

Don Isaac represented a new model of Jewish leadership, the powerful Jewish courtier who had the ear of kings, an international network and fabulous personal wealth. According to his biographer, Cedric Cohen-Skalli, he wrote his first work of philosophy, Ateret Zekanim to restore the reputation of the Israelite elders and nobles at Mount Sinai, whom Maimonides had portrayed in a negative light. Don Isaac did not see himself as a new Moses. But he did identify with the elders and nobles, the leaders of the nation, whose reputation he felt Maimonides had slighted.

Don Isaac finally settled in Venice in 1503. It seems that he went there with a specific purpose in mind, alert to a new financial opportunity. Five years earlier the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama had sailed down the west coast of Africa, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and discovered that India could be reached from Portugal by sea. His discovery meant that those engaged in the lucrative spice trade from India to Europe no longer needed to cross the Indian Ocean and endure a journey across the Arabian and Egyptian deserts before sailing homeward across the Mediterranean. Instead, they could ship their wares the whole way by boat, saving themselves time, money and considerable danger. But the new route threatened the Venetian economy; the city had grown prosperous and formidable as a seafaring nation, dominating trade between Europe and the East. Should the spice traders circumvent the Mediterranean, Venice would lose a considerable part of its income.

Venice’s setback was Don Isaac’s opportunity. Although he was estranged from the Portuguese court he believed he understood its workings, its interests and how to deal with it. He arrived in Venice to join his son Joseph and immediately sent a proposal to the Venetian rulers. He offered to send his son Joseph to mediate in the trade dispute that was blowing up between them and Portugal as a result of Vasco da Gama’s discovery. The Venetian government replied that they if he returned from Portugal with an agreement to which they could assent, Don Isaac could “rest assured that the gratitude of our State will not pass over him”.

It seems that Don Isaac was unsuccessful in negotiating a trade agreement with Portugal. But that hardly matters to his reputation. Intellectual powerhouse, diplomatic paragon, economic and financial luminary, Don Isaac Abarbanel was one of those people who excelled at whatever he turned his hand to. But perhaps his greatest skills were his ability to respond to adversity and to succeed, time and again, at the highest echelons of Christian society. As a Jew in the age of expulsions, forced conversions and inquisitions, that perhaps was the greatest skill of all.