One of the greatest challenges facing ethnic and cultural minorities is that of preserving their identity, keeping their unique traditions going and remaining distinct, while engaging with and living alongside the majority. Every minority has its strategies to achieve this, for Jews they include eating different foods so as not to mix socially, frowning upon intermarriage and adopting rituals that required them to gather together within their own community. But such strategies can only have a limited effect, the natural tendency is to take on the customs and lifestyles of the majority population, to become, to a greater or lesser degree, like everybody else.

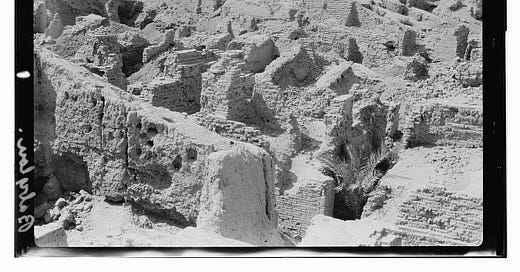

That helps explains why Tammuz, the month that has just begun in the Hebrew calendar, is named after a Babylonian deity. A god of fertility, Tammuz, or Damuzi, is first mentioned in Mesopotamian texts dating from 2500 BCE. The god obviously had some influence on Jewish exiles living in Babylon in the 6th century BCE because the biblical prophet Ezekiel, who lived among them, had a vision of the followers of Tammuz weeping at the gate of the Temple in Jerusalem. And the reason why we can be confident that the month of Tammuz is named after this particular god, is because the Jerusalem Talmud (the lesser known of the two Talmuds) says that when the exiles returned from Babylon they brought the names of the months with them.

The Babylonians named their months after Mesopotamian gods and, despite the Jewish opposition to idolatry, the Jews in Babylon had no difficulty in using these names. They had little choice really. When the exiles arrived in Babylon, they already had their own calendar. We know the names of several of their months from the Bible. But it would have been immensely impractical for them to keep to their own calendar while living, trading and working among people who used a different one. And, just as we don’t think twice about using days of the week named after the Norse gods Tiw, Wodin, Thor and Frigg, the exiles probably paid little attention to the origins of the calendar names they used.

Adopting the names of the months was a mild form of acculturation. More problematic, in the minds of some, was that the exiles also adopted the astrological symbolism of Babylon. Despite the biblical prohibitions against divination and fortune telling, archaeologists have uncovered ancient synagogues in Israel with mosaic floors depicting the signs of the zodiac. The synagogue at Hammat Tiberias even has an image of the sun god Helios at the centre of a mosaic circle, surrounded by the signs of the zodiac. There have been many attempts, none particularly convincing, trying to explain why these astrological mosaics are compatible with traditional Jewish belief. These attempts are hardly worth the effort, because in fact the astrological influence on Judaism runs far deeper than just a few decorative zodiac mosaics.

Take the Hebrew month of Tishri. Known in the Bible as Etanim, it may not be named after a foreign god; its name probably comes from an Akkadian root meaning beginning, because this is the month of the autumn equinox, considered to be the first month of the year. In the ancient synagogue zodiacs, Tishri corresponds to the zodiacal month of Libra, the sign for which is a pair of scales. The scales symbolise justice. Quite how justice fits into the astrological system is a matter for discussion, but justice fits very neatly into the month of Tishri. For Tishri is the month in which Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur fall, the period of repentance, during which it is traditionally believed the heavenly court decides our fate for the coming year.

There is no way of being certain whether it was the Jewish idea of Tishri as the month of justice which led the ancient astrologers to symbolise Libra with a pair of scales. Or more probably, whether the scales were part of a wider, regional tradition in which it was believed that one’s fate was decided at the onset of autumn; a tradition that then found its way into Judaism. It doesn’t really matter which way the influences flowed, the underlying point it that no society is hermetically sealed from those around it. Ideas and beliefs flow backwards and forwards between cultures.

The relationship between Tishri and Libra is not a coincidence. That is clear from the similarity between the Hebrew spring month of Nisan, and Aries, the zodiacal sign it corresponds to. Like Tishri, Nisan is the beginning of the year (a year can have more than one beginning — think of the school year, the calendar year, the tax year etc., all beginning at different times). The symbol for Aries is a ram, and Nisan is the month in which Passover falls, where in ancient times an elaborate meal was held, centred around the roasting of a lamb. Of course, a ram is not a lamb but the similarity is there. Additionally, the Babylonians held a festival in the month of Nisan, to their chief god, Marduk. The festival celebrates Marduk’s supreme power over all other gods. We see a similar idea in Passover, which commemorates the victory of the supreme, heavenly Deity over a human god- the Egyptian Pharaoh.

The most significant example of acculturation is when a minority population adopts the language of the majority and makes it their native tongue. Jews have been doing this for centuries: outside of the strictly religious communities few people today speak Yiddish as their first language and most of the world’s other ancient Jewish languages are preserved only by enthusiasts. The Babylonian Jews changed their language too. When they arrived in Babylon their language was Hebrew. By the time they left they were speaking Aramaic. This is quite obvious from the Jewish literature of the period. The biblical books written before the exile of 580 BCE were all written in Hebrew. Although some post-exilic books were written in Hebrew, the books of Ezra and Daniel contain substantial amounts of Aramaic; they would only have been intelligible to people familiar with the language.

Magic played a large part in Babylonian life, as did demons and other supernatural forces. They took longer to emerge as concepts in Jewish culture and by the time they did, other foreign influences were mingling with the Babylonian. By the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, a genre of magical and apocalyptical literature was emerging in Israelite society, books describing angelic encounters or world-changing events about to be unleashed by supernatural forces. The bible had made occasional references to angels but now these books introduced their readers to a crowded and complex supernatural world, full of good and bad forces which manipulated human lives and events on earth. These are Babylonian and other Middle Eastern ideas, expressed through a Hebrew lens.

Babylon was the first foreign society to exert a profound influence on Hebrew and Jewish culture. But it was only the beginning. Many of our customs and traditions today have been imported from the societies in which we have lived. The food we eat, the clothes we wear, the music in the synagogues, lighting a candle for departed souls, even some of our theological beliefs (though that is for another day). In fact, whatever our connection to our Jewish identity, the chances are, that to an impartial observer, our lives do not look very different from those of others.

Throughout history, Jews have managed both to retain their identity and fit in with the outside world, when we were allowed. It is that ability, to know when to adapt, and when not to, what to retain and what to abandon, that has helped ensure Jewish survival for so long.

.

I can find very little in Judaism that has not been adopted and in most cases (but not all, re-incarnation seems unchanged, for example) has been " Jewed" up, so to speak. as a polemic against what we shouldn't be.

The non-physical God, without geographical borders is a huge exception. I think Spinoza didn't comprehend the import of that.

One Sukkot Shabbat afternoon I gave a talk about the pagan roots of ushpizin. They wanted to assassinate me!

Shabbat Shalom

mb