Joseph Delmedigo was a worried man. His concern was that the new advances in science and astronomy happening in his lifetime were passing the Jews of Europe by. The vast majority of Jews lived in their own closed communities, shunned by the Christians in whose lands they lived and with no access to secular learning. It meant they were out of touch with the remarkable changes in scientific thinking that were taking place in the 17th century.

The world was on the brink of change. When Copernicus proved that the earth went around the sun, and not the other way round, it created an upheaval in the way people thought of the universe. New advances were continually being made in medicine, anatomy, chemistry and mathematics. The Church of course had rejected most of the new ideas, but at least they knew that change was in the air. Most Jews didn’t even know that changes were taking place. Joseph Delmedigo was one of very few Jews who was up to date with the new thinking and it worried him that there were so few other Jews like him.

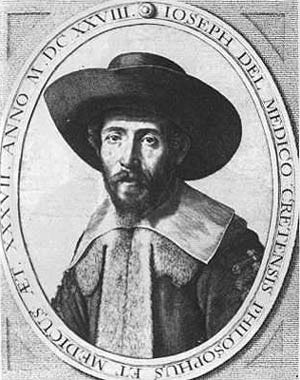

Joseph Solomon Delmedigo was born in 1591 on the island of Crete, known in those days as Candia. He came from a long and distinguished line of rabbis; one of his ancestors, Elijah Delmedigo, had been a renowned thinker who taught the works of Jewish philosophers to the Renaissance genius, Pico della Mirandola in Florence. The Delmedigo family had always taken an interest in secular education and when Joseph was just 15 years old he was sent to study medicine in the University of Padua, one of the very few educational establishments in Europe to admit Jews.

He did more in Padua than just study medicine, though he did qualify as a doctor. He probably also attended the town’s prominent yeshiva, or rabbinic collage, and certainly travelled to nearby Venice where he studied with Leone Modena and Simon Luzzatto, two rabbis whose intellectual interests extended far beyond the world of religious learning. Most importantly of all, the renowned astronomer Galileo was teaching at Padua University while Delmedigo was a student there. Delmedigo attended Galileo’s lectures and became one of the great astronomer’s favourite pupils. Galileo even allowed him to look at the heavens through his telescope, the most powerful in the world; it was a privilege that the astronomer rarely extended to others. For his part, Delmedigo called Galileo his ‘rabbi’.

After completing his studies Delmedigo returned to Candia where he practised as a doctor and rabbi. But he found the small island parochial; he was too intellectually curious to put up with its narrow insularity. He left Candia, never to return. He seems to have found the rabbinic world similarly suffocating, because although he was a rabbi, he shunned rabbinic company. When he left Candia he travelled to Cairo where he spent time with Jacob ben Alexander, the head of the Karaite community. The Karaites were Jews who rejected the views of the rabbis, interpreting the bible literally rather than following the Talmud as rabbinic Judaism did. Delmedigo’s rabbinic colleagues would not have approved of him interacting with Karaites; they did not appreciate that he was on an intellectual quest that was taking him beyond the scope of their knowledge. He studied with the Karaites and immersed himself in astronomy and mathematics, winning a public debate in Cairo with an Arab mathematician on the subject of spherical trigonometry.

Restless, Joseph Delmedigo did not remain in Cairo for long. He travelled to Constantinople where he met more Karaite scholars and then to Poland and Lithuania where there were also Karaite communities. He took a job for a few years as the personal physician to Prince Radziwill, then went to Hamburg, a city he did not like at all. He tried to set himself up with a medical practice but did not succeed; there were too many other doctors in the town. Fortuitously, the position of rabbi in Hamburg became vacant and for the first time in his life Joseph Delmedigo found himself employed in a religious role.

After Hamburg, Joseph Delmedigo, moved to Amsterdam where he took up the job of rabbi to an Amsterdam congregation. He became friendly with Menasseh ben Israel, a forward thinking rabbinic colleague, who encouraged Delmedigo to publish a book he had been working on.

Delmedigo’s book, Elim, one of only two he published in his lifetime, is primarily a collection of his scientific correspondence with a Karaite scholar, together with a certain amount of autobiographical material. He wrote it to expose Jewish readers to the scientific and mathematical ideas that he believed they should know about, covering topics from mathematics and astronomy to the occult and theology. It was dangerous stuff, his teacher Galileo had found himself in extreme difficulties with the Church authorities for demonstrating that the earth was not the centre of the universe. Delmedigo was about to have a similar, if less brutal, experience with the rabbis.

When Menasseh ben Israel’s colleagues heard that he was publishing Delmedigo’s Elim they set up a commission of enquiry to examine the text. Menasseh had anticipated this and had already arranged for a panel of four Venetian rabbis to review and approve the book. Two of the four rabbis on the panel were Delmedigo’s liberal minded teachers in Venice, Leone Modena and Simone Luzzatto. They approved the book, but did not know that Menasseh Ben Israel had not disclosed its full contents to them; he had not submitted the most contentious parts. A controversy ensued, more rabbis became involved, the secular leaders of the Amsterdam Jewish community weighed in and Delmedigo found himself at the centre of a storm. By the time Elim was finally published, his reputation in Amsterdam was thoroughly shot. He resigned his rabbinic post and left the city.

Controversy continued to dog Joseph Delmedigo. He moved to Frankfurt where he published a second book, Ta’alumot Hokhma, a defence of kabbalah. It was an astonishing thing to do. The last thing anyone could have imagined was that the rational, scientific thinker, Joseph Delmedigo, would write a book supporting superstitious, Jewish mystical tradition.

The Venetian rabbi, Leone Modena, who had approved Delmedigo’s Elim, was outraged. Modena was a fierce opponent of kabbalah and could not fathom why Delmedigo had written this book. Midway through the book however, Delmedigo had written:

“I am writing against the philosophers and on behalf of the kabbalists, since I was asked to do so by one of the dignitaries of the Jewish community whose heart is attracted at the moment to the Kabbalah. . . Should he be in a different mood by tomorrow and, entertaining a predilection for philosophy, ask me to praise and extol it, I shall eagerly undertake such a vigorous defence of it”.

This led Modena to understand that Joseph Delmedigo did not believe what he wrote; he was, as he said, simply writing the book as a commission for a patron.

Many people disagreed. They thought that his statement about being asked to write the book was deceitful. Even the Jewish Encyclopedia, published in 1906, nearly 300 years after Delmedigo lived, accused him of being insincere.

These days we realise that things aren’t so simple. Joseph Delmedigo was a scientist, but in the 17th century people still believed in many occult ideas; the transition from superstition to science took several generations. Even Isaac Newton was drawn to alchemy and to mystical speculation. It is quite possible that there was no contradiction in the mind of Joseph Delmedigo when he agreed to write a defence of the kabbalah. He was not being hypocritical, he thought there was a place for mysticism in the universe, alongside science.

Nevertheless, the publication of his second book did nothing to restore Delmedigo’s reputation in the Jewish world. He was now seen both as a supporter of heretical, scientific ideas that conflicted with religious tradition, and as a man whose views were inconsistent. He either wrote books that he didn’t believe in, or he was willing to adopt views one day that he had rejected the day before. One way or another, the consensus was Joseph Delmedigo was not a writer to be trusted.

Joseph Solomon Delmedigo disappeared from public view after his book on Kabbalah was published. Nothing more was heard of him for the last 20 years of his life. He ended his days in disappointment and poverty without having achieved his aim of encouraging Europe’s Jews to think scientifically.

He lived at the wrong time. Had he lived today, he wouldn’t be so disappointed. Jews play active, leadership roles in every scientific field. The idea that that the earth is the centre of the universe and that science is heresy disappeared a long time ago. Like many pioneers, Joseph Delmedigo did not live to see the fruits of his labours.