A few weeks ago, in a post for paid subscribers, I mentioned that several of the legends told by, or about, the 2nd century Rabbi Akiva bear a similarity to Aesop’s fables. Several readers have asked me to explain.

In ancient times, preachers and teachers often used parables or fables to illustrate a moral lesson or to explain a particular belief or way of understanding the world. This method is believed to have originated 4,000 years ago in Sumer, in Southern Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq. The Sumerians were the first people known to have had a written language, they were the most advanced civilisation of their time. It is largely due to them that we are able to read and write today.

The stories, proverbs and fables that the Sumerians told found their way into other Middle Eastern societies and across the Mediterranean. Many of their tales were about animals, whose lives were seen in some way to foreshadow those of humans. Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks and the various Semitic nations, including the Hebrews, all retold the Sumerian tales, recounting them in their own ways and adapting them to their own purposes. Historians speak of an ‘international tradition of folklore’.

When the ancient Hebrews, and the later rabbis, retold the ancient stories they picked out those that suited their religious purpose. They typically shortened them, so that only the bare bones remained. The earliest Hebrew use of one of these stories is probably the one in the biblical book of Amos (5,19), a prophet who lived in the Northern kingdom of Israel in the first half of the 8th century BCE.

Amos’s fable was adapted from an animal proverb of Sumerian origin: Upon escaping from the wild-ox, the wild-cow confronted me. Amos reformulated it, to warn his listeners that their behaviour meant they were about to be beset by calamity after calamity. He changed the Sumerian animals to those he was familiar with, he was a herdsman or shepherd, and the animals in his proverb are those which would have threatened the flocks he took care of: Like a man who was fleeing from a lion when a bear attacked him. Then he went into his house, placed his hand against the wall and a snake bit him.

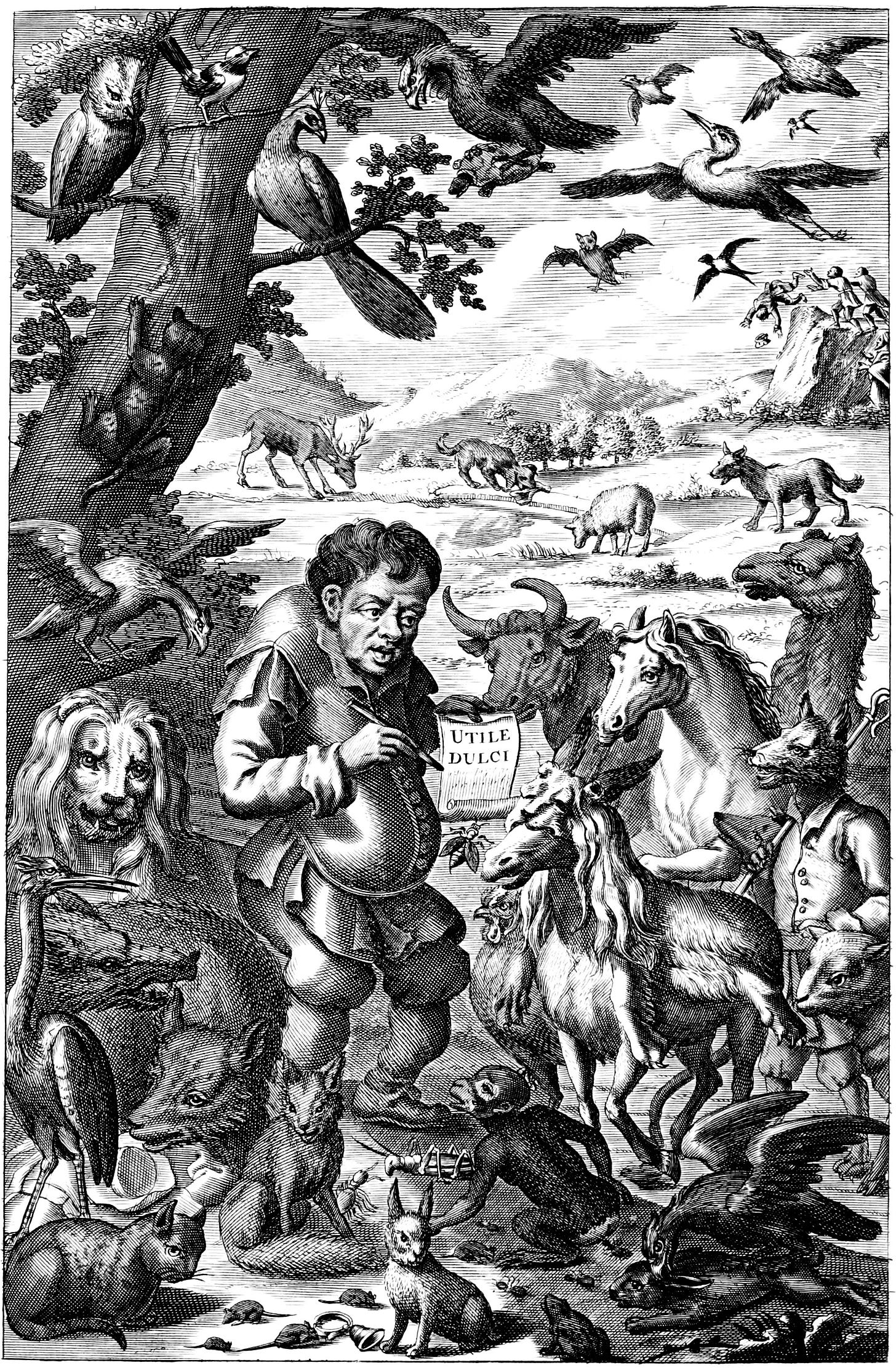

Amos’s parable predates Aesop’s fables by about 300 years. Who Aesop was, and whether he really existed, is a mystery, but in the 4th century BCE a collection of stories attributed to him was reproduced by the Greek orator, Demitrius of Phalerum. Demetrius’s work is now lost but it is thought that many of his stories were included in two later Aesop collections, one in Latin, made by Phaedrus in the 1st century BCE, and a slightly later Greek anthology, attributed to Babrius. These were the collections that would have inspired the Aesop-like stories which appear in later Jewish literature, those of Rabbi Akiva, his colleagues and his students.

One of Aesop’s fables concerns a lion and a boar who are both trying to drink from a well. They fight over which of them should drink first. Looking up, they see vultures circling. They immediately made up their quarrel, saying, “It is better for us to make friends, than to become the food of crows or vultures.”

This story, with changed animals, appears simply as a proverb in Armenian: Dogs quarrel among themselves, but against the wolf they are united. But in an early rabbinic version, first occurring in the 2nd century work Sifrei, it is used as a commentary on the story in the Bible of how the tribes of Moab and Midian had jointly conspired to curse the Israelites (Numbers, chapter 22). Elsewhere in the Bible the two tribes are described as enemies, so their alliance in this story must have appeared puzzling to some readers. The Hebrew parable explains why the two nations became allies: It is like two dogs that were fighting each other. A wolf attacked one of the them. The other one said ‘If I don’t help him, the wolf will kill him today and attack me tomorrow’. The two dogs joined together and killed the wolf.

The late Haim Schwarzbaum, who dedicated his scholarship to the study of folklore, showed how sometimes the Jewish tradition completely inverted the moral of an Aesop fable, to draw a conclusion directly opposed to the original. He quoted from a 1st century BCE Greek collection of Aesop:

A ship was smashed at sea and with it all its passengers sank to the depths. A certain man who saw what happened protested that the acts of the gods are unjust, for otherwise they would not have caused a whole ship full of passengers to drown on account of a single wicked person who happened to be on board. ‘Is it right,’ he asked, ‘that for the sake of punishing one wicked person, so many innocent human beings should be sent to destruction?’ While he was still speaking in this manner, a swarm of ants approached and covered the area around him. One ant bit the man and, enraged, he trampled the entire ant swarm. Then Hermes, the messenger of the gods, appeared and proclaimed to the man who had denounced the actions of the gods that he should consider his own behaviour. ‘Was it right for you to trample the entire swarm of ants on account of the one ant that bit you? So let mortals judge the gods justly when they pour out their wrath on so many innocent persons on account of one wicked man’s transgressions!’

When the ideas behind this story found their way into the Talmud, sometime between 300 and 500 CE, it was greatly shortened and given a very different moral:

Two merchants had planned to go on a business trip. One got stung in his leg and could not go. He began cursing and blaspheming. Some days later he heard that his friend’s ship had sunk and everyone was drowned. Now he thanked God for his good fortune.

Schwarzbaum points out that, “According to the Jewish legend the argument of the man who repented is quite logical, whereas in the Greek fable the example of the ants fails to answer why the gods punish the righteous on account of the misdeeds of the wicked.”[*] Copying a Greek legend did not commit the Jewish storytellers to endorsing its moral. They simply made use of its narrative for their own, very different purposes.

Many of Aesop’s fables are about foxes. Foxes are also ubiquitous in Jewish folklore; according to Rabbi Yohanan in the Talmud, Rabbi Meir, one of Akiva’s pupils, knew 300 parables about foxes. Yohanan however said that he only knew three of them. Fittingly though, the Akiva legend that most resembles an Aesop fable (though no direct parallel has been found) is also about foxes.

The background to the legend is that, when ancient Israel was under Roman rule, Rome had prohibited the teaching of Torah, under pain of death. Yet Akiva carried on teaching. His colleague Pappos asked him, ‘Are you not afraid of the Romans?’. Akiva replied with a parable:

It’s like a fox who was walking by a river when he saw fish swarming from place to place. He said to them, ‘What are you fleeing from?’ They said, ‘From the nets that fishermen throw over us’. The fox said, ‘Why don’t you come up to the land, and we will live together, just as my ancestors lived with your ancestors?’ The fish replied ‘Are you the one they call the wisest of animals? You are not wise; you are a fool. If in water, the place that gives us life, we are afraid, how much more afraid would we be on dry land, a place that causes our death?’

Akiva continued,

It is the same with us. (If we are afraid of the Romans) when we sit and study Torah, of which it is written: ‘It is your life, and the length of your days, how much more afraid would we be if we abandoned it?

Parables of this sort became one of the most frequently used methods through which Jewish religious teachers presented their messages to their audiences. The branch of early Hebrew literature known as Midrash is full of them. They also crop up frequently in the early books of the Christian bible, whose authors were of course Jews with their own message to convey. But while the contents of such parables are quintessentially Jewish, their origins of the genre date back much further. To the Sumerians, the long-forgotten people who taught the world how to read.